Hey there again. Hope you’re all well—or even better than well.

My very first post here at Call & Response considered why Maria Schneider’s “Pretty Road” might bring me back from dementia late in life. Her music is the stuff of inspiration for me. I couldn’t miss the Maria Schneider Orchestra’s Denver show last weekend.

The Maria Schneider Orchestra

Friday, May 3, Newman Center For The Performing Arts, Denver

I love it when artists from the rural Midwest unsettle the culturati by sharing the strange granularity or details of their lives. Such a moment came in the Maria Schneider Orchestra’s recent Denver concert when Maria introduced “American Crow,” a newer, unrecorded piece on the theme of political divisiveness.

In Maria’s Minnesota youth, she explained onstage, her parents kept a pair of crows as pets. These pets roamed about freely in the community until their mischievous nature turned them into local menaces. One day, authorities showed up at the family home demanding that the rascally birds be caged. So Maria grew up observing the caged crows and noticed a thing or two hundred about their behavior.

The cultured audience had seemed ready for, say, challenging avant-garde expressions. Less so for this quotidian bizarre. Two concertgoers in front of me exchanged a glance that said, “My Gawd, she’s speaking as if pet crows are as common as dogs.”

As “American Crow” began, though, the music more than convinced them. One of Maria’s great compositional achievements is making her experience accessible and even familiar to us through music. Her Midwestern-themed pieces like “Pretty Road” and “Thompson Fields,” for example, have persuaded worldwide listeners that the seemingly flat and empty U.S. heartland is rich in contour and meaning—at least to Maria. Her ability to make experience tangible in music relies on a practice of composing both an experience’s external setting and her internal sensation or feeling of it. Maria is about as programmatic as composers come. She introduces nearly every piece with a detailed narrative she intends a crowd to hear, even calling out specific characters for soloists. In Denver, she advised us that saxophonist Donny McCaslin would play “the daredevil” in “Hangliding,” a musical story of her own soaring flight from a cliff down a Rio beach.

Maria also succeeds by allowing her music unabashed beauty and romanticism. An apprentice of big band arrangers Gil Evans and Bob Brookmeyer, she’s surpassed them in orchestration skill, but even more so by extravagantly giving voice to her own enthusiasms. A pivotal early trip to Brazil immersed Maria in music that was both bright and sophisticated, emboldening her to reject the contemporary U.S. scene’s equation of seriousness with dark, brooding sounds. Her music is both pretty and dense, gorgeous and as serious as your life.

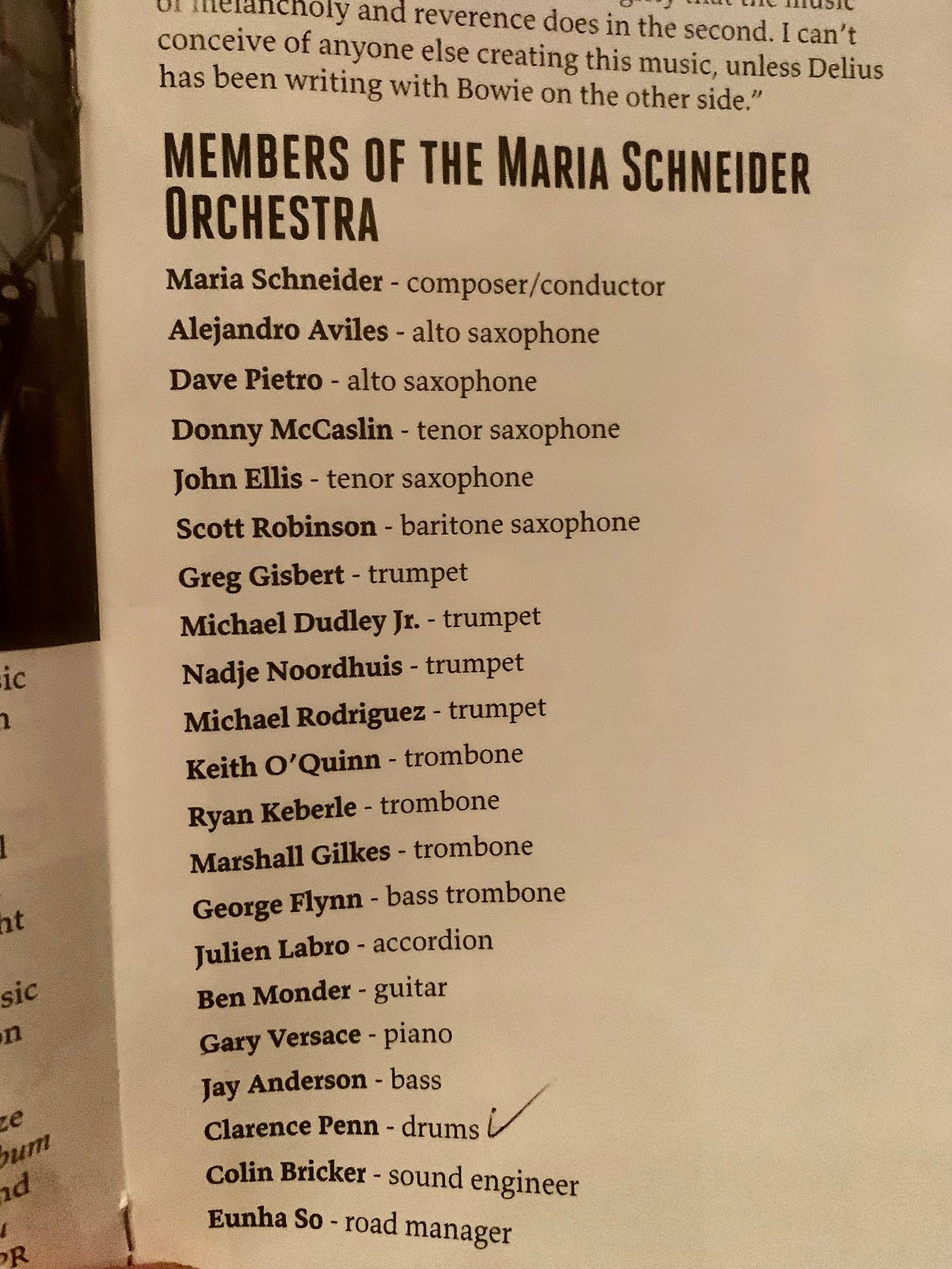

Risking such deliberate musical storytelling and unfettered beauty has gotten Maria a few critical dismissals as “too purple” or the like. Her approach meanwhile has been rewarded with numerous GRAMMY Awards, an NEA Jazz Master designation, and membership in both the Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Most important to the music, aiming for pure expression inspires Maria to use her 18-piece big band like a chamber orchestra and to compose for the creative voices in her group.

In Denver, Maria presented a cross-section of the orchestra’s 30 years of work, from the 1994 “Green Piece” to two new pieces, “American Crow” and “Reach.” Joining Maria were many musicians who’d been with her from the orchestra’s beginning. Maria’s band doesn’t see much turnover. Its newest member is accordionist Julien Labro, who joined up when Gary Versace moved from accordion to piano after her long-time pianist Frank Kimbrough passed away in 2020. The second-newest member is trumpeter Nadje Noordhuis, who took over the chair of her mentor Laurie Frink in 2015, after Frink’s passing.

After not seeing Maria perform for a few years, it was a pleasure to follow her expressive conducting again—she’s often compared to a painter brushing broad strokes of sound or a dancer summoning music with movement. It was profound to once again see such accomplished players content to step up for one virtuosic cameo-solo and otherwise play within the ensemble. They sat smiling at the solos of their bandmates or the driving rhythm section, never doubting the preciousness of making such sublime music. A Maria Schneider Orchestra concert is still part revival meeting, part repertory theater production, and part high-spirited jam session.

Back to “American Crow.” As Maria explained onstage, she watched her pet crows clamor and misbehave while she grew up in a happy household with a Republican mother and a Democrat father. She longs for those bygone days when communities and even single families had the courtesy to abide political differences. “American Crow” contrasts this earlier pax romana with the present day in which the masses crow that they’re right, right, right, refusing to listen.

Maria represented our current state of affairs as an initial cacophony of crows, with a mobbing of trumpets cawing in alarm. This gave way to a theme that Maria called Midwestern, a hymn that drew us into the sanity of the middle, a place of reflection where we seek to understand rather than be understood. Throughout the piece, Mike Rodriguez’s fluid trumpet played civil discourse, the sound of serenity in an age of anxiety. The music finally recalled that if crows are squawking menaces, they’ve also long been symbols of wisdom and transformation.

This Denver performance was the only time I’ve heard the unrecorded “American Crow.” Once was enough to hear the benefits of Maria’s uncompromising work with the same ensemble for decades: She connected the peculiarly personal to a social critique in instrumental music incisive, evocative, and lovely enough to reach everyone in the concert hall. Once was enough to hear a masterpiece offering clarion hope in the babel of a divisive age.

As Wayne Shorter told Maria, Miles Davis loved music that didn’t sound like music. The Maria Schneider Orchestra doesn’t play big band jazz tunes or even orchestral music per se. Her ensemble renders the very stuff of life into music. In Denver the other night, they gave us a dawn chorus. A piece of green. Thermal soaring. Stubborn delight in dense beauty. A diagnosis of what ails our culture. A prayer to accept the cure that lies within us all.

Maria’s latest album is Decades, a 3-LP vinyl box set.

Maria has tirelessly challenged the power of streaming and big-data companies.

For years I quietly hoped Maria would collaborate with Wayne Shorter. Now I’d like to put it out into the universe that I’d love to see her collaborate with Pat Metheny, a fellow Midwestern-raised master of jazz and beyond.

Thanks to Ann Braithwaite for arranging my comp tickets for this Denver show.

Love your reflections on this totally idiosyncratic bad ass. Saw her with the orchestra last year and good god, “Data Lords” just about gave me a heart attack. She’s a fucking brilliant shining light and a huge inspiration as an artist and person. Thanks for covering her and sharing your take!

“…emboldening her to reject the contemporary U.S. scene’s equation of seriousness with dark, brooding sounds.” Until “Data Lords.” She threw the black hat into the ring for that one. Appropriate for the emotional content of that music.