An Unexpected Interview with Songwriter Jimmy Webb

On Oklahoma, reckonings, and writing two songs in one

Not long before the pandemic shut us all down, I reported an NPR All Things Considered feature in Oklahoma City. This story considered OKC’s Blue Door, a beloved singer-songwriter venue and nerve center for blue politics in that deep red state. The piece aired in January 2020.

Back home in Colorado, I called the Oklahoma songwriter Jimmy Webb, a regular performer at the Blue Door. Some of you know Jimmy’s songwriting well, and maybe even read his 2017 memoir, The Cake and the Rain. All of you have heard Jimmy’s hits, or covers of them, like “Up, Up and Away,” “Wichita Lineman,” “Galveston,” and “Highwayman.”

We’d agreed to briefly discuss Oklahoma’s Blue Door for my NPR story, with Jimmy recording the conversation on his end. My side of this short interview didn’t even warrant recording, I assumed.

Professionalism demands that we observe any interview parameters set in advance. Yet because of my earnest interest in songwriting and the creative process, and even moreso because of the engaging, articulate, and extremely good human being Mr. Webb happens to be, we ended up speaking about much more. The interview went on five or six times as long as planned, encompassing subjects such as:

Oklahoma’s indigenous and Black history and the politics of its erasure

How Jimmy writes two songs at the same time, or has multiple themes going in a song at the same time

Ambiguity in listener reception to his songs

Political songwriting in the 1960s versus today

How the Highwomen’s 2019 adaptation of Jimmy’s song “Highwayman” opened his mind and heart on certain gender issues

Just before Jimmy and I started the interview, I shared this story with him.

I come from a Kansas farm just a couple hours north of Jimmy’s Elk City, Oklahoma hometown. It was during a family visit that I drove down to report on Oklahoma City’s Blue Door. My Dad took a keen interest in this reporting trip, calling me not long after I’d left to ask about the drive.

Me: “The dirt’s getting redder as I go south, but it’s hard to see under all the fog.”

Dad: “Oh, there’s fog? What’s it like?”

Me: “Not bad.”

Dad: “Is the fog curling up around the roadside in the ditches?”

Me: “It’s a fairly low fog, Dad.”

Dad: “But is it soupy? Is it the kind of fog that seems to hold rain up there in the air?”

Dad wouldn’t let me off the hook until I’d observed and described the fog well enough for him to picture it, thereby experiencing that moment with me on the road.

“I know you’ll come home with stories,” Dad said, as more of a command than a comment. In his milieu, someone journeying a couple hours south to talk with Oklahoma folks had a community duty, maybe even a sacred one, to bring home an account vivid enough to entertain and edify their family and friends.

Dad’s formal education was a short story. He’s also a perpetually curious person whose work with land and livestock allows ample time for reflection. Like many people in my and Jimmy Webb’s rural Midwest, Dad’s a lively storyteller.

When I told Jimmy about my heartlander Dad’s expectations for description and storytelling, it may have warmed Jimmy up to me a little. He knew then that he was talking to not just an NPR contributor who’d written a book about Joni Mitchell’s songwriting but also a farmgirl from up the road in Kansas.

At age 18, Jimmy moved to California and on to broad artistic influences. Still, the core of his songwriting heeded a call to witness for seemingly ordinary folks who happen to think extraordinary thoughts. Jimmy wrote songs like “Wichita Lineman” for my Dad, after all—and for you, me, and everybody.

My untaped side of the conversation appears here only occasionally and bracketed, a best guess based on my notes and memory. I’ll soon make the interview recording itself available to founding members.

Interview with Jimmy Webb

By phone, January 2020

Hello, Michelle. I'm real good. I'm real good. I just got back from about three months of touring and just enjoying some time at home with my one-eyed cat and my beautiful, intelligent and soon to be winging her way London Laura. She's leaving me. When I come home, she inevitably goes somewhere else. I dunno. There's gotta be a clue there.

MM: [Enthusing about Jimmy's wife Laura, a public television and documentary producer]

I'm very, very happy with her and we've been married 15 years and honest to God, it just doesn't seem like any time has passed at all.

MM: [The Blue Door, and how much Jimmy’s performances there have meant to Blue Door owner Greg Johnson over the years.]

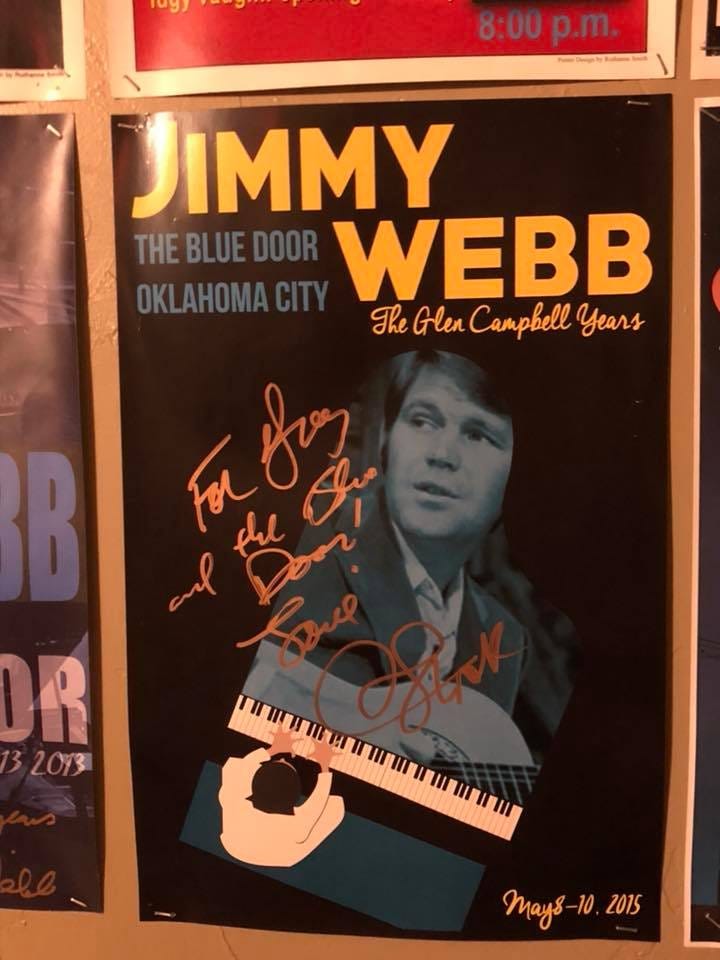

Well, that's so sweet. That really gives me a warm feeling because I love that little place and I've had some great nights in there myself with the local audience just sitting on those benches and calling out songs. And when I premiered my sort of multimedia or mixed media show that Laura produced called The Glen Campbell Years, I did it there. Everybody came out and we set up the screen and it was sort of like high school. It was like a special assembly or something. But they all helped me sort of shape up this mixed media show, now which has been running for a couple of years really successfully

I don't know whether Greg told you or not, but they used to make xithers there, which is a real kind of a prairie Gothic musical instrument. You know, it makes that real stringy sound and plays one big chord and it has a little fretboard you can pick out melodies on. But it was originally, believe it or not, a music instrument factory. It is basically a shotgun shack, you know, but it's been there a long time and it stands for something.

Me: [What all do you think the Blue Door stands for?]

It stands for, first of all, I think, a technical expertise in the songwriting field. So many great songwriters have come up through there and you know, their names are on the wall in the back. There's obviously a culture there which is very important, which is kind of a disappearing from the whole American blanket these little tiny clubs where it was possible for a songwriter to get started. Key words there are becoming rarer and more rare. So it stands for that. It stands for opportunity and excellence, expertise in your craft.

And then I think it's just impossible to talk about the Blue Door without talking about Greg's war with Oklahoma City University. And they have tried for so many years to bump him off of that little corner. The place is almost falling down. I mean, I don't know whether you noticed, but none of the doors are straight up and down and it's been rescued a couple of times. During the battle the predators always swoop in and say, you know, we'd really like to make that part of our campus. But it's sort of symbolic of university life that you have a coffee house, which is pretty much what it is, and it's a salon, a center of intellectual reflection and a place to listen to the hip or groovy records and songs of whatever that generation may be. So for that to stand there for 50 years is awesome.

Then I would say in a third aspect it is a lighthouse for liberal democratic thinking in a state that is really pervasively right.

All the sons and daughters of Oklahoma love her. But there's a kind of willful neglect of some of the history of the state and how it actually came together and how there's really no one in Oklahoma who isn't an immigrant except for some of the native Americans who live there. They have, they have the right to say, this is ours, this is our land. This has always been our land. Nobody else really has the right to do that.

So you start with that premise that this was originally land that belonged to the Native Americans and then you add in some of the some of the overlying historical events like the Trail of Tears when the army took all the Indians out of Florida and Louisiana and marched them to Oklahoma. So there's really a lot of sorrow. There's a lot of sadness there. If you stand out on the desert up in the panhandle when the sun's going down, you can hear it, you can feel it. You can feel those people, they still walk there and they're still on the trail of tears. So those kind of poetic expressions don't get you very far down the road with the average Oklahoman. The average Oklahoman has a pretty stable mindset about how the Indians weren't doing anything with the land anyway and at least we planted crops and introduced Christianity. And it's pretty much standard white European doctrine about why it's okay to go in and overrun less technological civilizations.

So for the Blue Door to disseminate a left wing . . . I mean, Jimmy Webb may have his name on a wall there a couple of times, but the true patron saint of the Blue Door is Woody Guthrie, and it is, I think, unashamedly and blatantly political.

MM: [I tell Jimmy I spoke to Choctaw American singer-songwriter and sometimes Blue Door performer Samantha Crain, who says that instead of writing more traditional protest songs in the style of Woody Guthrie, which can be too divisive at this moment, she favors what she calls the "Dolly Parton" method: singing individual stories of struggle, opening a door to broad identification and even empathy, as in her song “Elk City.” I posited that this also puts her in Jimmy’s tradition of protest songwriting]

Jimmy: Oh, I love that idea. I love it. You know, I'm embarrassed to admit this, but politically I was a little naive when I was growing up. In our little world where all the churches were white and the flowers were out front and people washed their cars before they came to church. I don't know whether anyone has mentioned to you that my father was a Baptist minister there for 27 years. I grew up in church and I grew up as one of the salt of the earth.

We were never shown anything bad and we were never really told about crime. We were never told except in a kind of a romantic way about the Trail of Tears. I'll give you an example. I didn't know about the Tulsa Race Massacre until I was 50 years old. I found a book in a store about it, which was a kind of holocaust. So in many ways the state has done a really good job of guarding its image. It's just something I think that was pretty much kept out of public view when the children were around and during religious services and what have you. I think there was a certain facade that was being presented to us as children, as we grew up in this perfect America with little houses in a row, people washing their cars, everything as it should be.

My father, I hasten to add, was a supporter of Martin Luther King. And as soon as the marches started in Selma and Reverend King came on the horizon, my father immediately begin planning joint worship services with black churches in our area. We had moved to California. I was thrilled because when the African American churches came over, they brought their drums and their basses and their amplifiers and that gospel, you know, rhythm and soul. I was into it. All of a sudden, like, church became a real entertainment for me. My father also had a very hard-line policy towards any kind of LGBT discrimination in our church. Now I know this sounds incredible, but this was 1964 in Colton, California. Day by day my father grows in my eyes, because he knew what was happening and he took a stand and he lost dozens of deacons over things like allowing in this one openly gay couple, one black, one white, who used to come and sit in the front row.

There were people who wanted to run them out of the church. And my father said, “Well, you know, I'll resign, but they're staying.” So I just want to underline that, because my father was not a hater.

I can remember my father preaching pretty virulently in Oklahoma about John F. Kennedy. That if John F. Kennedy was elected president, he would take his orders from the Pope, which was pretty much standard fare from the Southern Baptist convention. They had sort of sent out a memo to all the preachers that was the party line on John F. Kennedy. And then my mother fell desperately ill with a brain tumor and she ended up, as fate would have it, or God would have it, she ended up in St. John's hospital, a Catholic hospital.

And my father was telling me one night about how the nuns took care of her and he was weeping in a public place because he could not believe how much the nuns loved her and how much the nuns ministered to her as she laid dying with no hope of recovery. And, and so, you know, my father is an interesting figure in all of this. I write about him in my book because he was a man kind of torn between two worlds. But I really think he came down on the right side of history.

He was somebody that you didn't want to tangle with. And by the way, that's our friend Greg Johnson at the Blue Door as well. You don't want to tangle with him either. He's got some really strong beliefs and if you don't like it, you can leave the club and you can never come back.

MM: [I describe a discussion that happened around one of Jimmy’s songs at my family's Thanksgiving. When I mentioned to the fam that I was going to talk to Oklahoma songwriters, including Jimmy, someone brought up “Galveston” as a great patriotic song. Somebody else, one of my younger nieces, said no, it was a song about a soldier who didn't want to be in the war anymore. It's interesting that a song like "Galveston" could be open to nearly opposite interpretations. Did Jimmy have any thoughts about that?]

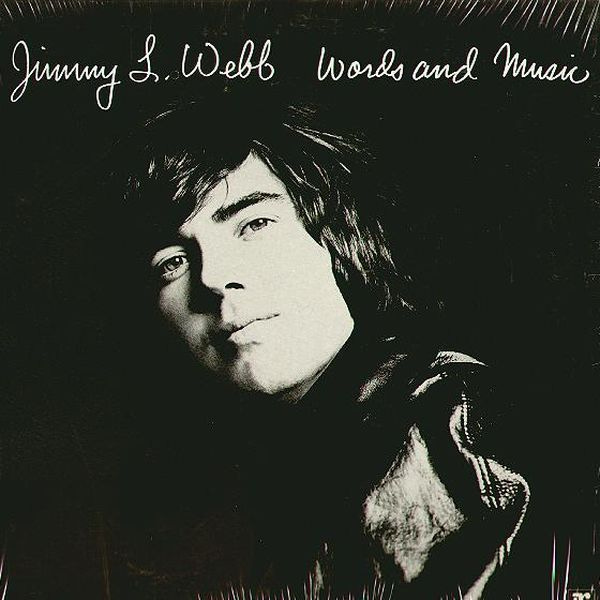

Well yes, particularly I do, because I do that song at every show, virtually, and it was not written as a patriotic song. Glen performed it like a patriotic song and did such a fine job that we ended up with a hit record. If you hear my version and you can, on my album Letters, that's the original treatment of the song, which was very elegaic. And it was clear--the antiwar sentiment, if you will. "Anti-war" is not a dirty word, for crying out loud, as some would have you believe.

It was clear to Vietnam vets because they come up to me after the shows some nights and just quickly grab my hand. They don't want to be seen, they don't want to make a big deal--sweetly though, give me a hug, whisper in my ear and say, "Thanks for writing that song, man, that really got me through." I'm not saying that to brag, but I am saying it to point out that it also depends on your perspective. So the guys who were actually in that predicament, they got it loud and clear. They understood what it was about. People from outside the conflict, civilians, they may have wondered about what the song was about, but there doesn't seem to be a lot of confusion in the foxhole about what it was about.

Me: [I'm interested in the remake of "Highwayman" by the Highwomen]

As you know the Highwomen are Amanda Shires, Brandi Carlile, Maren Morris, and Natalie Hemby. Originally Sheryl Crow was I think supposed to be in the group.

It's worked out amazingly for me. It's really one of the more interesting songwriting stories in my opinion. Because not long after the song was a hit in the mid-eighties, I began to get requests from women who wanted to record the song. I think I must have made a lot of faces, you know, because it was like this is just like not a gender-friendly song. This is about guys, you know, like rough, tough, oil men and people like that.

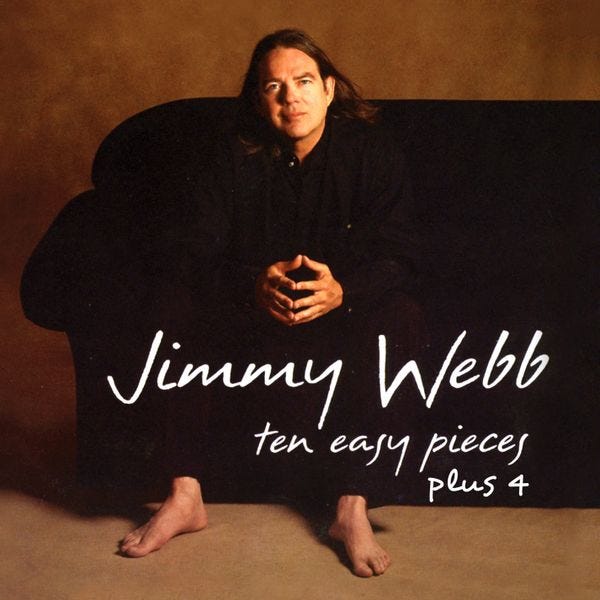

The only subtle context was that it had two songs at the same time . . that's something that I do and have done. So there was one song that was just about, you could say, a kind of metaphor for a strapping young country, America, you know, that starts out as a high whim and then becomes a seafaring nation and it becomes a bridge-building nation. So there's that surface, "We're the men who built this country" song. Then just beneath it, there's a song about reincarnation. There's a song about coming back and living different lives, that we'll all be back again. I think that it was a complex song to begin with.

And even though I won a Grammy Award for Country Song of the Year, Waylon Jennings said to me one time, "Which country's that?" A really funny guy. I loved him like a brother.

People like Jane Olivor, she said, "Can I do the song? Can I do Highwayman?" I had no control over that at all. But I think I told somebody, "Tell her that she can't do it." It's silly now because the world has changed so much. And I said, "Tell her that she could do it, but she's gonna have to make up her own version cause I'm not going to write another lyric." So that was a long time ago. And then Judy Collins has been singing it for years and she just sings it in the masculine gender. She just sings it like she's a man and everything she does is lovely anyway. And in fact, it's on her new album, Winter Stories.

So now these ladies [The Highwomen] come, and I'm kind of tired of the whole subject. I said, "Just tell them to do whatever they want." And Laura said, "Are you sure about that?" I said yeah. And they wrote this haunting lyric about a woman attempting to get her baby, her child across the Rio Grande and into America where the child might have hopes for a better life or something to look forward to.

The first time I heard it, I broke down and cried in my kitchen with Laura. She put her arms around me cause it just tore me up because I thought, here I am sitting on my bed and I'm not doing anything. I'm not doing anything. And these women took this song that was basically old and tired and emasculated, really, and probably not long for this world, and they turned it into, well, a number one record for one thing, but they also turned it into a new anthem along the lines of "Deportee," you know, Woody Guthrie's great one. I thought how lucky I was that these women came my way and blessed me with their lyrics from my song.

I was just deeply moved by it and reminded that when we were at our peak, and I'm speaking about my generation, when we were at our peak in the mid-sixties to mid-seventies, we wrote message songs. I think I learned that at Motown because that was my first gig. They used to say, "Yeah Jimmy, but what's the message?" Pound it into my head. "Don't be writin' a song about nothin', now. It's gotta be about somethin'." Some of those basic things seem to have gone by the by in the current kind of what I would describe as cotton candy popular music.

I don't want to get letters. Because I realize that Lady Gaga and Adele and many other people have written songs that stood up for political causes. And that rap itself is a political statement from a segment of society that has cause to be angry and has cause to their frustration with the way things are going in this country. And I sympathize.

But I think that pop songs, melodic songs should . . . I mean, if ever a country needed a kind of a compendium to the events of each day, we need a musical compendium that comments on the politics and the missteps and some of the tragedies of this world that seems to just be like a carousel that's out of control, that's gonna eventually fly off its base and go rolling through the amusement park.

Everything is just so crazy and there's a remarkable lack of comment from the writers, I think. Because there's more going on now and there's more to write about politically and it's more out in the open than it ever was in the 60s. And here's all these flagrant violations of human rights and common decency and, and, you know, we can go on and on and on, from various players and bad actors all over the place. And yet we don't hear a lot of music about it the way we would have. "Four Dead in Ohio." We don't hear that.

So it bothers me a little bit because I know what a strong tool music can be in the struggle to make America a better country and to give everybody a fair shot at their pursuit of happiness. I know that that's the way, that's the way [Blue Door owner] Greg Johnson feels and that ultimately at the center of all this. The center of all this is are we just gonna keep going the way we're going, folks, you know? Or are we going to try to change things? And, in a way, I think we're about to find out. I think this 2020 election is gonna shed enormous illumination on that question as to whether we are going to just continue the way we've always kind of muddled along and make change in very, very small increments. You know, it seems like I always drift into politics whether I want to or not.

Me: [I could talk to you all day, Jimmy, but we’ve already talked so much longer than we’d planned to. You’re way late for your next appointment. Anyway, having your voice in here means a lot to the story but also to Greg.]

Well, he means a lot to me. He and my brother went to OBU together. Yeah, they were in the same class. My brother was the big athlete. He went on a basketball scholarship. I don't know how Greg got there. I don't think it was a basketball scholarship, but he got a fire in his belly when he was that age and he's still holding up the end of the liberal Democrats . . . and there are a few liberal Democrats in Oklahoma.

Me: [Thanks and farewell]

Remembering Ohio 5/4/70

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q7Ohc7kQh5U

I grew up musically in the 60's with The Beatles and The Who in one ear and Top 40 radio so it was impossible to miss Jimmy Webb's great songs. I still tear up at "Wichita Lineman". Yes, he was a craftsman but he also wrote from the heart. There's magic in there! Thanks for sharing! And for the variety of videos in the post!