First When There’s Nothing

Evolving notions of so-called giftedness and how singing a big 80s hit saved me from perfectionism at age 11

Hello again, dear readers. Many of you will relate to this essay.

First When There’s Nothing

I felt a gut punch when I saw it. Not that it was meant for me. But Mrs. Shinn’s handwritten awards list was sitting out there on her desk. Deciphering my teacher’s scrawl had become second nature after reading her chalkboard cursive throughout the sixth-grade school year.

I’d approached Mrs. Shinn to ask if I could find a piano to practice my song for the talent show, the event that would follow the sixth-grade awards ceremony the next day. Both events marked the end of elementary school for my class.

Mrs. Shinn noticed me staring at the awards list and covered it with her hand too late. My name was next to an award for the highest standardized test score. Since that award was based on an external measure, she had to give me that one. It was my only award of the eight or so listed. My face burned with the shame of being caught staring at her private list. My face burned with the shame of not seeing my name next to more awards.

“Don’t snoop,” Mrs. Shinn said, looking up through her glasses, her hair dyed and set in a brown halo identical to my grandmother’s. They probably had the same stylist in our rural Kansas town. “How can I help you?”

“I’m done with math and reading,” I said. “Can I go practice my talent show song?”

“Go ahead,” Mrs. Shinn said. “I need you out of my hair.”

The classroom went blurry. As I headed back to my desk, it was hard to move my feet. Meanwhile, my thoughts raced as I catastrophized my disappointment in that awards list. At the start of sixth grade, I’d resolved to do everything right. Instead of making trouble or distracting my friends from their schoolwork when I finished mine too early, as I had in fourth and fifth grade, I’d tried to be a model student for Mrs. Shinn. Sitting quietly while I waited for classmates to finish the assignments I’d rushed through. When I had a chance to help younger kids with reading, I developed strategies to assist them.

None of my efforts mattered. Mrs. Shinn didn’t recognize them. One student was receiving three awards, so it wasn’t as if my teacher had distributed them among students as widely as possible. She’d rejected me.

If I’d confided my despair to anyone, they may have reasoned that not every student got an award—this was true in 1984—so I should be happy with one. They might have said these honors would naturally reflect the teacher’s favoritism for certain students, but had no bearing on my essential worthiness.

To be clear, I was no genius wunderkind. But like many “fast learners,” as teachers then referred to us, I suffered from perfectionism. Perfectionism is not about striving to be perfect so much as never feeling good enough. Shame prevented me from discussing my awards disappointment with anyone. With my rigid focus on my inadequacy, it would have been impossible to entertain broader considerations, anyway.

I was 11: my world was absolute. Back at my desk, the practice session for the talent show was abandoned. What was the point? Nothing mattered anymore.

Deep inside your mind

Now, with the evolution of so-called gifted programs, this scene would play out differently. We’ve had a fundamental shift from viewing giftedness as purely cerebral to understanding it as an interplay of intellectual, emotional, and social elements that require broad support.

At age nine, my fourth grade teacher sent me for testing with a blue-eyed, bearded man whose clean, groomed fingernails were entirely unlike those of the farming men I knew. He stared at me too intently as he gave me a long series of tests.

“In verbal ability—that’s reading comprehension, grammar, and spelling—you could be in college, Michelle.” The testing man said my name too often. “You scored well into high school in math and logic skills. For a fourth grader, that’s also good. But unfortunately you tested, well . . . retarded in spatial reasoning, Michelle. That was the horse puzzle I asked you to do. A big issue was your attitude when you had trouble with the puzzle—you showed no problem-solving skills and just gave up. So I won’t be working with you, Michelle.”

It was true. I couldn’t find a horse in those puzzle pieces to save my life. At the time, disqualification for poor spatial reasoning made perfect sense to me. My Dad frequently told me how awful I was at identifying the right tool for a repair job, an inconvenient weakness on a farm. Those practical skills, it was often repeated, were more valuable than any “book learning.”

Right around this time, Howard Gardner was developing his theory of multiple intelligences, which was revolutionary in establishing that children could be highly intelligent in one area while average or below average in others. A poor showing in spatial reasoning no longer disqualifies a student from specialized educational opportunities if they show advanced math, verbal, and logic ability. Also, the late 20th century brought recognition that gifted children may be at increased risk for certain emotional challenges because of “asynchronous development,” or uneven intellectual and emotional maturity.

My ‘80s rural Kansas school had no dedicated gifted track at all. Fast learners could annoy overburdened teachers, who had trouble keeping us busy in the classroom. Excelling in school elicited frustration from some teachers. “It’s too easy for you,” Mrs. Shinn said to me once, handing back a test with a perfect score. “It means more when kids work for their grades.” This comment was quite reasonable from her perspective and also should have told me I wouldn’t be sweeping the sixth-grade awards that year. Mrs. Shinn had saintly patience for fast learning compared to a nun who’d taught me previously at the Catholic school.

Still, I might not trade my 1980s treatment as a fast learner for today’s approach. The enlightened understanding of gifted kids being at risk for certain emotional challenges has now escalated into what I see as a pathologizing of gifted kids, an overcorrection in which a fast learner is presumed to have emotional problems. Giftedness is now often viewed as kind of disability in need of special accommodation at every turn. The pendulum has swung too far in the other direction.

One bright kid I know sits alone reading in the SUV on every family visit to the park, because socializing or even just reading among others disturbs him too much. Encouraging a gifted child to relate to others in a healthy way has somehow become tantamount to denying their gifts. And while expanded programs for special learners are generally a positive development, the now-thriving gifted kid industry can exploit busy parents with large incomes. What parent wouldn’t shell out money for a program that assures them their middle schooler’s meltdowns are a natural byproduct of exceptional intelligence rather than the result of poor parenting?

When I was growing up, social gatherings were occasions for everyone to warm ourselves at the fire of human companionship, even when oversensitivity made some of us want to hang back. “Put that book down and go play with the other kids a while,” all parents would insist. And rather than adults presuming my high test scores came with debilitating emotional problems, I received a strong message that they were in fact a gift. “You can go to college and do anything with scores like that,” teachers would say to me. Messages like these helped me get to college as a first-generation student.

Of course, that sense of responsibility to do something significant with my ability also contributed to my harsh self-judgment. At 11, I was stumbling right into the pitfalls of perfectionism.

A slow glowing dream

On the morning of the sixth-grade awards ceremony and school talent show, my Mom yelled into the farmhouse bedroom I shared with three younger siblings: “Time to get up!” I’d been awake for a couple of hours, ever since my Dad had left the house to milk cows at 4:30 a.m. Lying in the predawn dark, I’d convinced myself that maintaining a neutral expression during the awards presentation would be impossible. By the time my Mom called into the bedroom, I had a plan.

“Mom, I’m sick,” I announced.

“That’s too bad, on the last day of school,” she said. “You probably have some fun stuff to do today.”

Isolating myself was better than exposing my shameful underperformance at the awards presentation. It was a classic perfectionist construct: all or nothing at all.

But withdrawal, as usual, offered no real escape. Avoidance only created a vacuum, drawing my attention to exactly what I was trying to avoid: I kept thinking about the awards presentation. Besides, the morning’s momentum was with my younger siblings and their healthy participation in the last day of school. When I got up to help my little sister Carrie find a missing shirt, I almost got dressed for school myself. The humiliation of showing my face at the awards presentation sent me back to my fake sickbed on the couch.

After the yellow school bus roared away from the farm with my relatively well-adjusted siblings, I went to the bookshelf for Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, a book I loved and reread like holy gospel. A comfort read. It was probably the 20th time I’d devoured it since I was seven.

Our gold rotary phone rang on the wall. “Why is the phone cord always so tangled?” Mom complained in my general direction. She answered after the third ring.

“Yes, this is she,” Mom said in her polite phone voice.

“She is?”

“Okay, I’ll see. Thanks for the call.”

“Honey, that was Mrs. Hemberger-Lange,” Mom said. Mrs. Hemberger-Lange was my elementary school music teacher.

“She noticed you weren’t at the ceremony to get an award. You’re supposed to sing in the talent show soon? She used the word ‘headliner!’ So she’s hoping you can still make it to school.”

“It’s too late,” I said, not looking up from my book.

“Mrs. Hemberger-Lange said it’s not,” my Mom said. “I could take you.”

She walked to the kitchen where I heard her turn on the faucet to fill the sink with dishwater. In the 80s, kids rarely shared the events of the day with our parents, let alone our emotional lives. Parents had to be astute, even psychic, to understand kids’ motivations and inner conflicts. If my Mom had no idea why exactly I was skipping school, she now understood my sickness was a cover for troubled avoidance. She also knew I loved music.

The dishwater stopped running. Mom walked across the living room’s gold shag carpet and sat beside me on the couch.

“Michelle,” she said. “If you perform in the talent show today, you can wear makeup.”

Makeup wasn’t supposed to be on the table until I was 13. Mom had strict ages for the commencement of privileges like leg-shaving, makeup, and dating. This talent show makeup exemption at 11 would cost her big; my younger sisters would beg for their own early privileges.

I stood and looked at the rumpled sheets of my fake sickbed on the couch. Makeup would transform me into another version of myself. What version, I wasn’t sure. Anyone besides Big Awards Ceremony Loser was fine with me.

“Just some eyeshadow and blush!” my Mom called after me. I was already halfway down the hall to the makeup tray in her bedroom.

Being's believing

My Mom pulled our mud-stained sedan up to the elementary school. She dropped me off with a cheery “Good luck!” Like most 80s parents, she never considered coming inside for the talent show. The office secretary’s eyes widened when I presented my garish face at check-in, the light blue eyeshadow and bright pink blush heaped on as if it were my last chance to wear makeup instead of my first.

Across the hallway from the office, the talent show was underway in the multipurpose room. After the show, there would be just enough time to clear out chairs and pull tables down from the walls for lunch before the space would be emptied for PE classes. Everything mundane and extraordinary happened in the multi-purpose room. It smelled like cafeteria food, sweat, disinfectant, and ambition, a confused bouquet of its many purposes.

“Michelle, you got an award!” a fifth grader whispered when she saw me enter the room. “Awesome job! But you weren’t here to get it. Hey, are you wearing makeup?” Understanding came in an epiphany: Normal people didn’t consider it a failure to win one award when there were only a handful of them on offer. As a supposed fast learner, I could be slow to pick up on common sense.

Nervousness prevented me from focusing on the talent show performances before mine. I did proudly register my younger sister Jenny playing Air Supply’s “Making Love Out of Nothing at All” as an instrumental on the piano. No one advised Jenny that another song selection might be more appropriate for a fifth grader. At 10, my sister probably still didn’t know what “making love” was, anyway. She was lucky. Reading The Thorn Birds had helped me connect some of the dots about the facts of life. Sensing it was time for the talk, my Mom then opened the World Book Encyclopedia to the “sexuality” entry with its genitalia drawings, giving me the shocking full picture. “This is how you’ll have a baby one day!” Mom had said. When she left the room, I vomited on the open encyclopedia.

Mrs. Hemberger-Lange interrupted my reverie. “Michelle, you look green,” she said. “Don’t be nervous. You just didn’t have time to warm up. Go outside in the sun and sing the first verse of your piece. Breathe.”

I slipped out of the multi-purpose room’s side door with my piano/voice/guitar sheet music for “Flashdance . . . What a Feeling.” The song had been released over a year before, in March 1983, a month before the film Flashdance. It was co-written and performed by Irene Cara, who’d emerged as a star in the 1980 film Fame.

With its star power, movie tie-in, and stirring message of self-empowerment, “What a Feeling” became a massive hit in 1983, reaching #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and staying there for weeks. I was one of thousands of girls who sang it in talent shows the following year.

Mrs. Hemberger-Lange opened the door to tell me it was time. She’d insisted I not accompany myself on piano to focus on “full expression” in my singing. So she’d approximate the recording’s layered synthesizers on the piano herself. As I approached the stage, she pulled me aside.

“If you decide to take the chorus in your chest voice today, pull the mic away from your mouth a little,” she whispered.

In “What a Feeling,” the vocalist moves from verses in a lower register to choruses of soaring high notes. I’d never managed to take the chorus in my chest voice, always playing it safe by shifting to my thinner head voice.

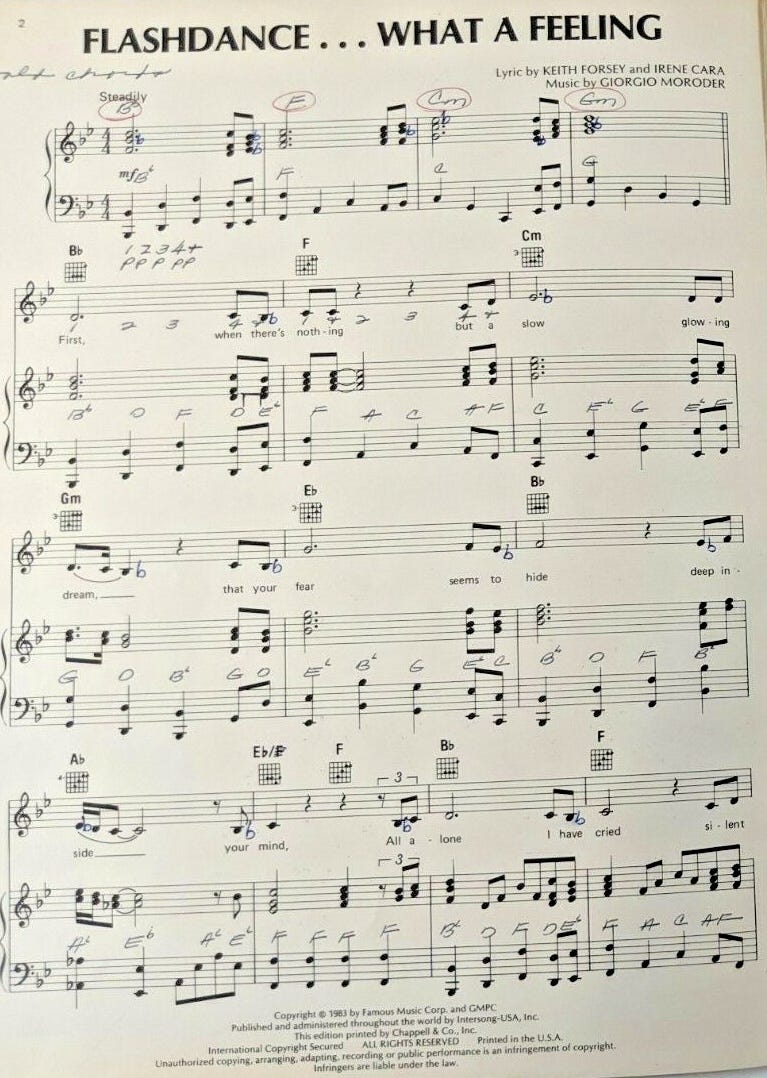

“First when there’s nothing but a slow glowing dream,” I started.

As much as I emulated Irene Cara’s performance of the song, my vocals fell short of her richness, charisma, and range. I had no brilliant future as a solo singer.

Yet any 11-year-old who sings in time and tune with a clear, pretty voice tends to impress. Stand out. I felt a shift in the crowd’s attention with my first few notes. It helped that they recognized the song.

“All alone I have cried/silent tears full of pride” I sang, my volume rising. Tears full of pride were exactly what had kept me from the awards ceremony, I realized. The only thing left to do was pour myself into the song more fully than I ever had before.

It was time for the chorus. I took a deep breath.

“What a feeling!” I sang. “Being’s believing.” Somehow, I’d remained in my chest voice as I made the leap to the chorus’s high notes and emotional peak. It was surprising, this first sense of more being possible in a heightened musical state. Mrs. Hemberger-Lange smiled and struck the piano keys harder to match my volume and intensity.

We dialed it back down for the next verse. “Now I hear the music . . .” I looked at the crowd. Some students and teachers seemed confused to see the Michelle they knew so well performing in a persona they didn’t quite recognize. I remember Mrs. Shinn sitting in the audience with her mouth agape, but my memory is probably embellished by all the ‘80s movies in which teachers who underestimated students got their comeuppance.

As the verse’s tension built to the chorus’s triumphant release again, I started to feel strange. It was as if my consciousness were extending beyond my body, so that I was watching myself perform onstage. This observing self found it funny that I’d ever worried about awards and noted the irony of me singing “I’m dancing for my life” when I was only managing a stiff shuffle onstage as I sang: left foot to right foot, then right to left. More than anything, this observing self recognized that when I went all out, taking my passion and making it happen, as the song said, perfection was irrelevant. I looked from the stage to see my favorite teacher, Mrs. Means, smiling as if she were in on this big cosmic joke. Maybe she was.

After the performance, I needed to be alone. A bathroom stall with a closed door offered the only privacy in the elementary school. The music had charged me with so much possibility that it felt like the bathroom walls were expanding and contracting with my breath. So what if I wasn’t the teacher’s favorite? Endless roles existed beyond that conventional one. And transcendent states of being were better than any award. If I could just get out of my own way, I might experience more of them.

A rush of relief and self-acceptance brought tears to my eyes, muddying my pink and blue makeup. I stepped out of the stall to wipe my face with a rough brown paper towel. I didn’t need makeup to feel like someone else anymore. Beyond the limits of perfection, we all contain multitudes.

What a feeling

After the talent show came a hot lunch that we were all too overstimulated to eat. Then our last recess. Dawn, Danielle, Amy, and I walked around the playground reliving grade school memories. Younger kids who had yet to develop self-consciousness called out praise: “Michelle, I loved your song!”

I stuck close to my friends, those girls who wanted me beside them no matter what I’d won, lost, or sung. We walked past the windbreak where we’d huddled together playing hand-clap games. Past playground equipment where we’d all fallen and sprained something because there were no soft landings on blacktop asphalt.

Les and Robbie were standing in their usual spot against the fence. Robbie’s jeans were highwaters, ending three inches above the top of his sneakers. I looked around: Most of us had outgrown our jeans that year.

“Did you hear her sing?” Robbie asked Les, pointing at me as if I weren’t only 12 feet away.

“My Mom can sing better than Michelle!” Les yelled loudly enough for everyone on the playground to hear.

That could be true, I thought. I’ve never heard Les’s Mom sing. Maybe she sings like Irene Cara. Pushing through my perfectionism had landed me in a philosophical frame of mind. Granted me a kind of equanimity. Besides, nobody could touch what music had stirred inside me onstage. It felt like music had occupied my very bloodstream, achieving the communion I’d hoped for when I accepted a wafer on my tongue from the priest during Catholic mass. Schoolyard insults would bruise me again, but not that day.

My friends and I walked to the end of the playground blacktop where an open grassy field began. Going beyond the blacktop was forbidden. On that final day of elementary school, we stepped onto the grass anyway, testing our freedom.

“Can you believe we’ll be in junior high next year?” Dawn asked.

It’s gonna be totally awesome, we all agreed. A little too quickly.

“Michelle, your makeup came off, but you still look different,” Danielle observed.

“I know,” I said.

With thanks to Thelma Shinn, Karen Hemberger-Lange, my Mom, and Irene Cara.

That's a wonderfully insightful piece, Michelle, and it resonated deeply with me. Like you, I was lopsided in those aptitude tests delivered in my middle school. School record in verbal skills, 7th percentile in spatial relations and something called "mechanical reasoning". I remember the guidance counselor asking me, "Son, didn't you ever want to take something apart and put it back together?" (No, I didn't).

I was a video producer in one of my various careers, and had the occasion to do a series of documentaries on the gifted ed program in Vancouver elementary schools. We interviewed many kids and their teachers, in an attempt to help other teachers in the system understand the program and the students more completely. The kids were amazing! They loved learning... certain things. Others bored them silly. And they were insightful. They disdained the material they were supposed to regurgitate without a deeper understanding of the subject.

Years later, when *everything* somehow became political, the program was cancelled. It was seen to be elitist by decision-makers, and somehow, deprived others of similar educational experiences. I lamented, and thought of the many kids who were no longer given the chance to pursue their passions.

Great writing, Michelle - thanks!

Lovely, heartbreaking and uplifting all at once. Thanks for this.