Guitarist, Interrupted: Conversation and Cocktails with Johnny Smith, Part One

A first-anniversary post for Call & Response!

Guitarist Johnny Smith was the humblest star I’ve ever met. Probably because he left behind stardom at 36 for the relative obscurity of another life.

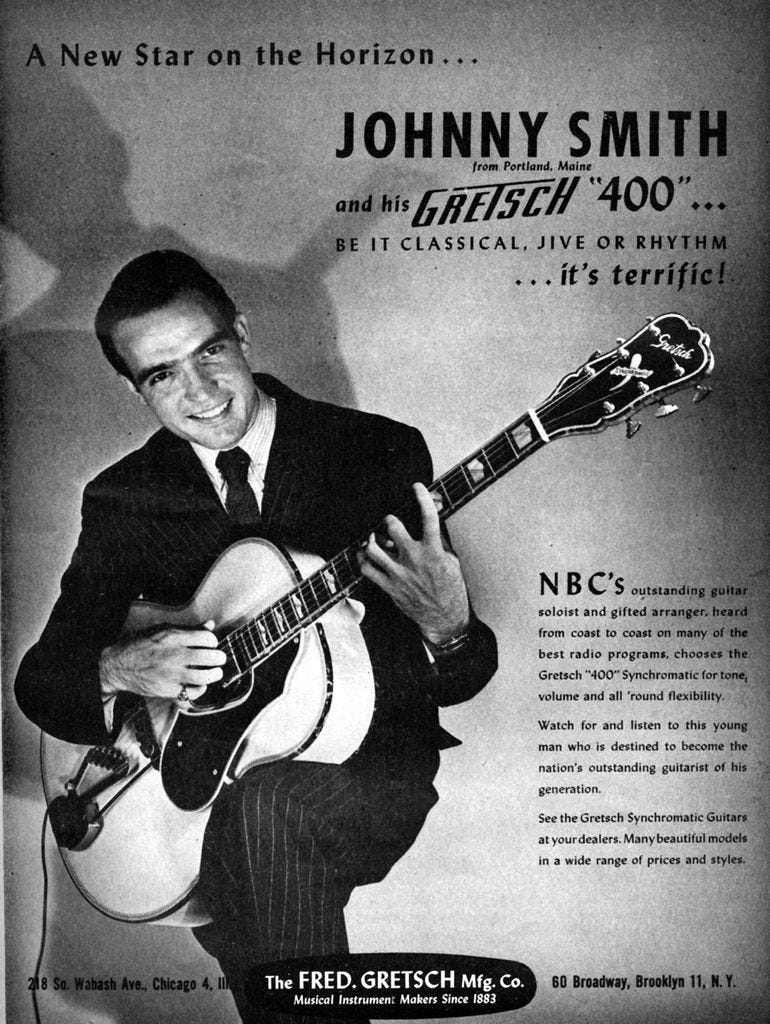

From 1946-1958, Johnny Smith was a staff guitarist for NBC by day and a New York jazz musician by night. He survived playing under authoritarian conductor Arturo Toscanini, sight-read Schoenberg with Dimitri Mitropoulos, was underpaid by Benny Goodman, and worked with Mary Lou Williams and Stan Getz. Charlie Parker liked to check Johnny out when he played at Birdland. Johnny’s 1952 interpretation of “Moonlight in Vermont” was voted Downbeat magazine’s Jazz Record of the Year. He was making the scene.

Then Johnny’s wife died in 1958. Unwilling to leave his preschool-aged daughter with a sitter while he worked day and night, Johnny moved near his family in Colorado Springs, where he played locally and toured occasionally. He wasn’t idle in Colorado. He opened a guitar store, taught lessons (including to a young Bill Frisell), designed some classic guitars, and had a surprise hit when The Ventures recorded his tune, “Walk, Don’t Run.” Still, Johnny disappeared from New York in his prime. For the rest of his life, he was as well-known for leaving a thriving career as he was for anything he recorded or played. Johnny passed away in 2013 at age 90.

I spent a memorable afternoon with Johnny at his Colorado Springs home in 2009. We enjoyed conversation both before and after cocktail hour. Some writers present their Johnny Smith interviews as rare access to a recluse. As far as I can tell, he made himself widely available for interviews. Bill Milkowski wrote a strong Overdue Ovation piece on Smith for Jazz Times back in 2003. Chip Stern spoke with Johnny on the phone regularly and has hours of compelling interview material. You can watch a 2005 video interview here, courtesy of the NAMM folks. Here’s Johnny telling a quick Django Reinhardt story back in 1999.

By the time we spoke, Johnny was 87 and slowing down. What distinguishes my interview, especially Part Two, is the presence of guitarist Alan Joseph, Johnny’s friend and fan (Alan also was a bandmate of my now-husband). Alan helped take our conversation places it may not have gone otherwise. He was a social lubricant, putting everyone at ease and brightening the mood. Johnny was relaxed enough here, for example, to mention how Bud Powell could become violent without a handler on the scene. He complained a little about fly fishing with his great-grandchild. I love getting close enough to artists to hear them talk like real people and know their humanity.

As of today, we’ve been meeting here at Call & Response for a full year. Thank you! Here’s why I’m celebrating my first Substack anniversary with this interview. After Johnny and I spoke, I pitched a few editors a story. With no new Johnny Smith recording or major event at the time, they couldn’t use it. This interview was exiled to my archives alongside dozens of other unheard gems. Thanks to your support, Substack writers are no longer beholden to release schedules, strict topicality, or even the zeitgeist. Here our work doesn’t live or die by the news peg. We can share an interview or story simply because it’s fascinating. We can present people as the true characters they are or were. We can stretch out into new creative forms.

In Colorado Springs, Johnny enjoyed a more well-rounded life than he had as a busy New York musician, a shift that relates to recent Call & Response posts on artists moving to smaller, more affordable cities. As I prepared this interview for you, I was struck by a moment when Johnny said, “When I had to leave” and quickly corrected himself: “I didn’t have to. When I decided to leave New York and come out here . . .” Viewing even a tragic situation as an opportunity for a better life was key to Johnny’s personality.

Johnny witnessed Colorado Springs’ growth from a town of 89,000 in 1958 to a city of 600,000 when he passed in 2013. Before we begin the proper interview, I’ll share some audio from the very end of my visit when we were well into cocktail hour. Johnny sang an original ditty about urban sprawl called “It’s Beginning to Look A Lot Like Denver” to the tune of “It’s Beginning to Look A Lot Like Christmas.” (Explicit language warning)

Please find full interview audio at the post’s end, after the paywall

Guitarist, Interrupted: Conversation and Cocktails with Johnny Smith, Part One

Michelle, pointing to the wall behind Johnny's home bar: First of all, I have to know where these dollar bills come from.

Johnny: Well, if you have a drink, your first drink will cost you a dollar, signed, and then that pays you up for life. You never get charged again. So all of these came from people that have had drinks at this bar. Yeah. So fire away.

Michelle: We should probably cover some of your basic story.

Johnny: You know, I have to apologize, Michelle. I'm a little hard of hearing. I have a hearing aid, but I hate the damn thing. And so if you don't mind projecting a little bit.

Michelle: Oh no, I can definitely project. I will do that happily. So I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about your childhood and how you started playing music.

Johnny: Well, during the Depression, my folks, I was born in Birmingham, Alabama. And during the Depression, my dad had to go wherever he could find a job, which was like New Orleans, Chattanooga. And from Chattanooga, we migrated to Maine, Portland, Maine, where I continued to grow up and started playing with a hillbilly band when I was 14 and traveling all over the state. I never graduated from high school. I was busy playing and helping the folks, you know. And I was making the huge amount of four dollars a night, which was big money then.

And after when the war broke out, that's World War II, which you don't remember. I went into the Air Corps and I was supposed to have been a pilot but my left eye took care of that and I ended up tooting a trumpet in the band. And after the war I went back to Portland and the program director at a radio station that I was playing at took an air check down to NBC in New York and I got a call to come to New York and so I was with NBC and the different networks.

Michelle: So you never took a lesson?

Johnny: No. The main reason was there were no teachers. Had there been I would have walked 20 miles to learn a new hold(?) on the guitar but there were no teachers and I guess the radio was probably my best teacher. Listening to the big bands and everything.

Michelle: What was it like for you as a boy moving from down south all the way up to Maine?

Johnny: Oh, it was a big disappointment because I expected to see igloos and got off the train. I didn't see any igloos, so I was devastated, you know, because I certainly expected to see some Eskimos and igloos, but anyway.

Michelle: Okay, so by virtue of your talent, you got a job at NBC, and as I understand it, at NBC, you had to be able to read any piece of music.

Johnny: Yeah. Well, I give credit to the service. When they flunked me flying, they sent me over to the band barracks. And the old band director gave me an Arban's book and a cornet and told me to get in a latrine and I had two weeks to build a lip. And it was that or the other decision was if I didn't get in a band they were going to ship me to Biloxi, Mississippi for a mechanic school. And believe me that was quite a motivation. It was because of the Air Corps I had to learn to read and that saved my rear end when I got on staff [at NBC] because everything was written out, you know, music. And you had to play whatever was thrown in front of you.

Michelle: Is it because you could play everything [all musical styles] that you never called yourself a jazz musician? I think most people, when they think of you, they think jazz guitar legend. But you never called yourself a jazz musician?

Johnny: Well, I still don't and I firmly believe that I'm not. I had to be involved. There were so many different types of music. I had another problem. I loved to fly. And so right after the war, I started flying and got all my ratings, the commercial pilot, flight instructor. And I was very serious about that. And I have an instructor for single and multi-engine. And it's an ATP, which is an airline transport pilot, which all the captains have to have. So it was very serious with me. And that was another excuse for not dedicating my life to playing. So therefore, I don't claim to be a jazz guitarist, playing like Alan Joseph. And I was just too diversified. And I loved to go deep sea fishing. When I had to leave, I didn't have to. But when I decided to leave New York and come out here, it was like a Shangri-La because all the areas where you can hunt big game and everything. I hope this don't get you off the air, but I'm kind of like fly manure. I'm all over the place.

Michelle (laughing): You had a lot of different interests and capabilities. But it seems like there were a lot of people in New York City who took you pretty seriously as a jazz musician. Do you think there's a special kind of intelligence that’s required to play jazz?

Johnny: No. Well, I shouldn't say no. Certainly, being a jazz musician, it is very demanding. I mean, to be an accomplished jazz musician goes far beyond being able to plunk on the guitar. You have to have all the knowledge and repertoire and everything. When I was in New York, I did work with the NBC Symphony under Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic. One of my favorite stories is one night I finished playing in Birdland at four o 'clock in the morning. At nine o 'clock that morning, I was sitting in the middle of the New York Philharmonic. And that's quite a contrast. But I was so fortunate to have been in New York at the very apex of live music. I guess those days are gone forever, but I was so fortunate because my childhood dream, one of them, was to be able to be in the company of great musicians. And of course that was fulfilled with New York.

Michelle: How did you get Stan Getz into your band? How did you guys get together for those recordings that you made?

It’s been months since I’ve offered anything special to paid subscribers. The rest of this interview transcript as well as the audio are beyond the paywall. Thanks for your support!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Call & Response to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.