Hard Truths for Poor Artists, Part 3: I Owe My Soul to the Higher Ed Store

The forced error of student loans and the double bind of college for poor artists

Enjoying this newsletter? Thank you for reading! Please help support my writing on arts and culture by becoming a free or paid subscriber. I’m awfully close to a paid subscriber milestone that will put a checkmark next to my name, giving my work greater visibility here on Substack.

A note on that ahhhhtist term

My use of the word artist is designed to make this Hard Truth series more widely relevant. In real life, I don’t walk around calling myself an artist, which would be insufferably pretentious. I call myself a writer—which also can be insufferably pretentious, depending on one’s inflection.

Onward with Part 3 in the series. To recap: Last summer’s online response to editor, novelist, and adjunct professor Molly McGhee’s poverty tweets inspired me to write about the topic of money and work for poor artists. Parts 1 and 2 are foundational, including my working definition of poor, a discussion of generational wealth, and much more. Part 4 is still to come.

The forced error of student loans

Today, more than half of students leave school with some student loan debt. President Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan has stimulated some vigorous discussion in recent years. Loans for students in the arts still deserve special attention. To underline the obvious: Debt repayment puts us in a position of needing to earn more money. Since artistic work tends to be more inconsistent and lower paying than work in other fields, student loan debt can push even accomplished artists out of artistic careers.

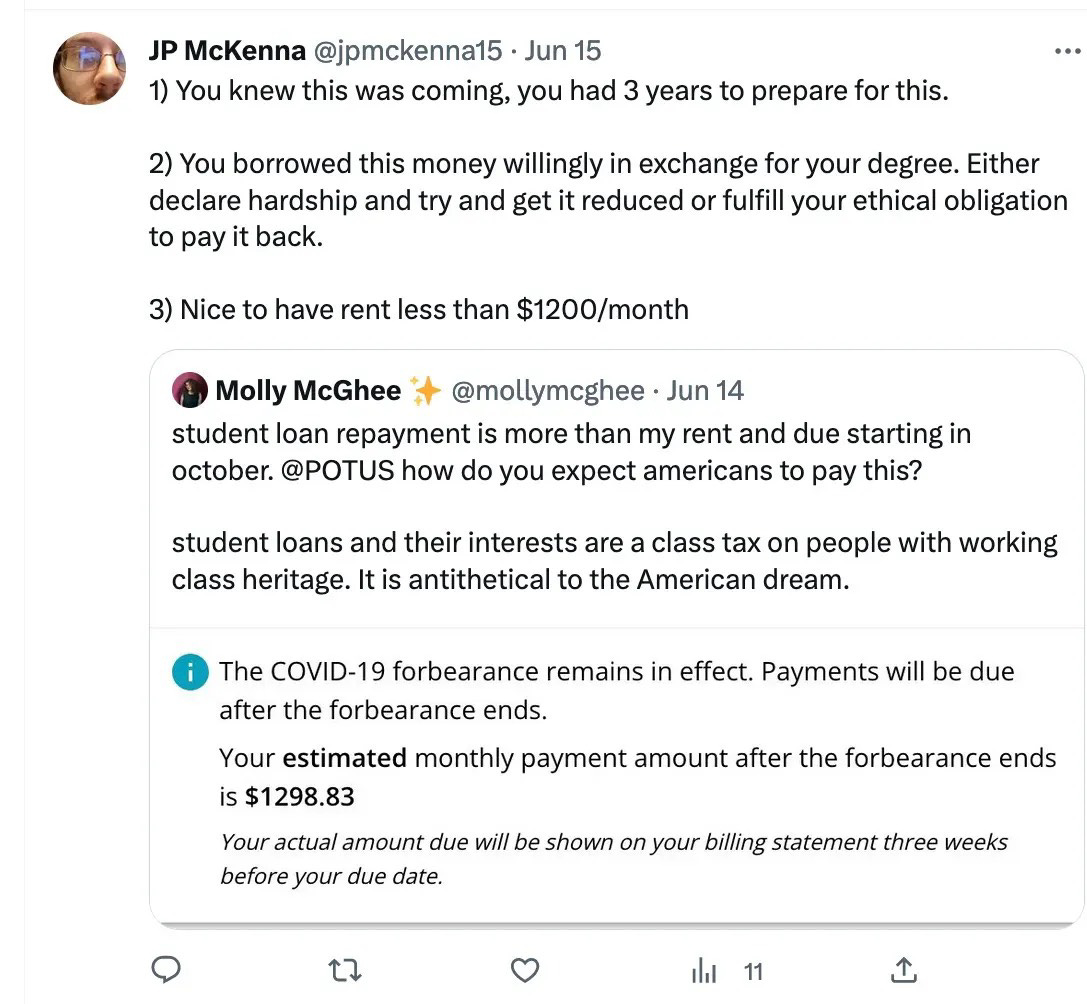

Last summer, Molly addressed student loans on Twitter.

The numbers, quickly. In another tweet, Molly said her income was $45,000 a year. After taxes, she probably takes home $36,000, or about $3,000 a month. If her rent is, say, $1150, and her student loan payment is $1300, the balance would barely cover utilities and food. Income-based repayment could bring Molly’s monthly student loan payment down considerably but won’t change her bottom line: She’ll still owe the full loan amount and can’t build a middle-class financial life.

The overall response to Molly’s student loan tweet was not sympathetic. Student loan debt is often attributed to poor judgment or even profound character flaws. Another representative comment:

“People make life choices based, presumably, on their values. They decide to prioritize creativity or freedom over economic security. That’s totally cool, but then don’t expect people who chose differently to subsidize you.”

For poor students, though, I see student loan debt as less of a choice and more of a forced error. I’ll explain.

Researchers have found that people who weigh in on student loans tend to come from more privileged backgrounds. Arguments of borrowers sacrificing economic security for creativity often assume that all students know economic security. Many poor students don’t. Home can be a crowded place of overdrafts and broken dreams where economic security is a distant notion. School, by contrast, is an accessible, well-ordered space; in lieu of economic security, academic achievement can give poor kids a sense of stability or meaning.

People who criticize student loan borrowers also often imagine borrowers with the college preparation and guidance they had themselves. Poor kids’ families may have no understanding of college at all. It never occurred to me or my family, for example, to study for the ACT; I didn’t even take the SAT. My rural Kansas high school wasn’t much help, either. I sought advice on my prospects from the school guidance counselor, who gave me a career finder questionnaire. When I indicated comfort with rising early and working alone, the questionnaire found that I should be a baker. It didn’t sound so bad. I was ready to accept doughnut-making as my fate until a friend reminded me that someone with my test scores, G.P.A., and interests usually went to college.

A few letters from prestigious colleges turning up in my rural route mailbox certainly didn’t make it feel possible for me to attend one. In the early 90s, I couldn’t even look schools up on the internet. For me, those colleges were off the map, the stuff of fiction. So my senior year of high school, I sat cross-legged on our farmhouse’s outdated gold shag carpet typing application forms to state universities and essays for a couple of scholarships. With no models or guidance for how to proceed, I imagined people in suits, like Frasier from the 80s sitcom Cheers, bored after already reading hundreds of essays and looking for a diverting read.

I landed at the University of Kansas, where I lived in a scholarship hall, the cheapest housing on campus. On my first day there, my roommate glanced in my closet and asked when my parents were bringing my clothes. I told her I’d already unpacked. She laughed and said she and a friend were going to the Gap later but obviously, I couldn’t afford to shop there. That was true. I looked into shopping at the Gap when Joni Mitchell, whom I adored, modeled for a company ad.

An assigned “big sister” soon sat me down in the scholarship hall.

Big sister: “They say financial status matters as much as academics for getting into the schol halls but most of the girls here don’t need to work.”

Me: “I’ve always worked.” I had. Helping out on the family farm from age seven, plus babysitting, lifeguarding, scooping ice cream, and in my senior year of high school, filling vending machines—driving a big truck with candy and chips from location to location, gifting family and friends the expired treats that I was supposed to throw away.

Big sister: “What’s your situation here at school? Are your parents supporting you?”

Me: “I have some scholarships for tuition.”

Big sister: “Yeah. Me too. But since you’re not living with your parents now, you have more expenses: food, housing, clothes, shampoo, toothpaste. Plus money for any fun you want to have! What did your family say about living expenses?”

Me: “Nothing. We didn’t talk about it.”

Big sister: “Okay, well, it sounds like you’re supporting yourself now, Michelle.”

It was the first time I heard this reality from anyone. My family and I had been busy feeling lucky that I was going to college at all. No one would be quite so clueless just a couple of years later when the internet democratized information and some basic Webcrawler searches taught all prospective students a thing or two about college and its costs in advance. Happily, too, first-generation students like me are now identified for targeted support as they head to college. We even have our own acronym: FGLI for First-Generation, Low-Income. I’ll use it here.

FGLI students still arrive at school without the social-cultural capital of kids whose parents went to college. The challenge of navigating coursework and college life independently can trip up any new student. FGLI students’ considerable social and financial obstacles can throw them into a culture shock tailspin—not an ideal state in which to make student loan decisions that will impact the rest of their lives. First-generation, low-income students often are thrust into a middle-class-or-higher college culture so different from their home lives that student loan money might as well be a Monopoly game’s candy-colored cash.

I had many jobs during college. At university and public libraries, a dorm kitchen, a convenience store, a health food store, a garden center, a women’s resource center where I programmed a lecture series, and an antique market’s Ethnic Fashions booth, where as a white girl in a batik headwrap, I recited information from my African Studies classes and sold little.

To get through college without loans, even working scholarship students need moral support or other guidance. First-generation, low-income students usually don’t have it. If we require a bicycle to get to our minimum-wage job, any vague misgivings about borrowing money for it are overwhelmed by pressing need. We can’t text our parents for advice on loans or anything else related to college. No cosigner is required for federal student loans. We have faith in college financial aid staff, who look like authority figures to 19-year-olds and rarely if ever ask us how we’ll pay a loan back. If FGLI students do glance at any future payment charts, the monthly amounts seem feasible, because everything in life is still feasible at 19, and because interest doesn’t figure into those projected payments. Debt may be all too familiar to poor students, anyway.

Besides, for FGLI students, merit feels like its own collateral. If through high test scores or sheer hard work we managed to get into college, we believe we can pay back loans, too. Merit can then create its own need. When poor students receive an invitation to participate in a special summer program, we may not know how to weigh its value to our education. We take out yet another loan for it. Merit got us where we are, so merit-based opportunities must be taken and financed at any cost. These values can lead us right into expensive grad school programs.

For first-generation, low-income students who want to play the game of college, the forced error of student loans is almost inevitable.

College and its loans are a class tax on poor artists

Molly calls student loans a “class tax” on people with a working-class heritage, one that’s antithetical to the American dream. This class tax has special meaning for students in the arts.

First, let me address a common question. If someone needs student loans, why would they pursue a precarious artistic career instead of something steady and lucrative while enjoying art on the side? One answer is that some of us don’t realize we can do art on the side. First-generation, low-income students typically aren’t acquainted with, say, bankers who write fan fiction or chiropractors who play jazz gigs. College professors may be our only white-collar professional models when we decide on a major. We can’t text parents for insights on choosing a major. So one charismatic professor telling us we have a gift for one of the arts may be all it takes to turn our passion into a career.

Back to college loans as a “class tax.” Part of what we’re buying with college loans is acculturation to the middle or upper classes. For example, poor and working-class families tend not to discuss current events or ideas at home. No one was reading the Times or Post on our family farm, where we subscribed to Hoard’s Dairyman. No one was expected to have an opinion at supper beyond whether we wanted cheese on our burger (this is an important thing, though—no cheese, thank you). If anyone had shared an idea about art, they would have been laughed from the table and told to have their head examined.

Middle and upper-class folks do tend to discuss ideas and current events. A liberal arts education teaches students of all backgrounds and in all fields how to engage with the wider world. This ability is even more vital in the arts, where self-expression is the key to the kingdom. Believing we have ideas worth formulating, expressing, and sharing enables everything from writing essays to staging pop-up performances. College gives FGLI kids a seat at the table. It gives us a voice at the table, too—if we persevere long enough. I was in college two years before I mustered the courage to raise my hand in a classroom. (A few years back, the First Generation Foundation reported that only 11 percent of first-generation, low-income students had earned a bachelor’s degree after six years, compared to 55 percent of continuing-generation students).

College is where FGLI arts students become versed in cultural references and get comfortable moving among artists: talking about books and music, going to gallery openings, having dinner with a visiting artist after a workshop. Without years of undergrad and grad school, I never would have been competent or confident working at the NPR bureau, hanging at jazz clubs, teaching college writing myself, or having lunch with the literati at Tina Brown’s maisonette.

Worth mentioning here is how high tuition and the internet have collaborated to create new paths into arts and arts-related careers. A sound engineer recently told me he’d never go to school and pay to acquire a skill that he could learn for free on YouTube. Still, bypassing college or other training programs requires the authority and ability to learn on one’s own, which kids may or may not have.

I still hope to somehow send my 12-year-old son to college. Given current earning trends in the arts, I can’t suggest artistic pursuits to him as anything but an enriching hobby. Still, if my kid were to work as a professional artist, he wouldn’t need college as much as Molly and I did. My husband and I have work and interests that model close engagement with books, music, and museums, with arts and culture of all kinds. Seeing us do creative work gives our son agency in the arts. When he won a songwriting contest at age 10, more impressive to me than any lyrical or musical skill was his empowerment to write an original song as a fourth grader. Our kid slid right past self-doubt and self-consciousness into focused creation. At an art opening, symphony concert, or open mic, he’ll talk to anyone, asking questions, making jokes, and sharing what he knows. It’s second nature to him. My son would be better off with money for college, whatever his major, but the socio side of his socioeconomic status is already giving him some valuable hard and soft skills for the arts and beyond.

Kids like Molly and I do need college to gain the skill and confidence for artistic work and to adapt to artistic milieux. This puts poor artists in a double bind: We need student loans to build professional lives, but can’t have solid financial lives once we have loans. Rather than asking why Molly chose to encumber herself with student loan debt, we should be asking why anyone needs to burden themselves for the same access to the arts as others.

Recent years have seen some fledgling student debt strike movements, to which I’m partly sympathetic. I’ll close with a relevant anecdote from way back. Though I’m fuzzy on some details, the story’s broad strokes are correct.

The Ghostwriter Who Ghosted His Student Loans

Not long after I moved to New York in 1998, I spent a weekend in the Maine home of a ghostwriter. I’ll call him John. As a friend and I drove to John’s place, we made a wrong turn somewhere. I suggested a phone call for directions.

My friend explained that John never answered his phone because he was evading his student loan lender. An error in John’s social security number on his student loan applications put him in an unusual position: the lender couldn’t pin the unpaid loans to John, thus preventing any negative showing on his credit report (this situation would be impossible in today’s digitized, hyper-connected world). A certain loan representative, however, was on a crusade to track John down and hold his feet to the payback fire.

With his good credit intact, John moved from New York to Maine, buying a fixer house on a bay and working to pay it off before he addressed his student loans. This son of working-class immigrants had an admirable work ethic, waking at 4:30 a.m. every morning of his life to research and ghostwrite the books of a household-name author. 12-hour writing days were common for John. His remaining hours were devoted to home renovation, often with reclaimed material he hunted down himself.

At dinner, I asked John a dumb question: Did he regret his student loans?

“Of course!” John said. “Don’t you? Everyone does! We have no idea what those loans even mean when we’re 18 or 19. Though I couldn’t do my ghostwriting job without that education, so . . .”

That double bind. The clerical error on John’s loan application created a loophole, opening a window of possibility for him to own a home and maybe move into the middle class. Meanwhile, loan interest was accruing, inflating his balance. But by putting home ownership first, John was, in a way, correcting the forced error of student loans before he spent the rest of his life paying for it.

Many would say John’s course of action was wrong, even unethical. I say he was smart to use a rare loophole in a system that creates so much trouble for so many of us.

This was a long one. Thanks for reading. For next week, I’ve been working on Hard Truths for Poor Artists Part 4, which involves the story of my working life as a writer, some advantages of being a poor artist, minor pitfalls for poor artists, and my two big career mistakes, getting an MFA (when I already had an MA, book deals, and a college teaching job!) and moving away from a cultural capital. Telling this story is a delicate business.

Warning-long comment!

Michelle, I am so grateful for your insightful examination of this topic. I find myself gulping down your posts, reassuring myself that I’ll go back later for closer reading. I definitely can see sharing excerpts of them with my students at PSU.

As I often do when I read your posts, I reflect on the difference in perspective that race throws into the mix. In this case I’m asking myself how it is that my father, the youngest of 12, son of a sharecropper, got himself to college, an engineering degree, and a boost to the middle class. So that his son could attend a music conservatory, and his grandson, an Ivy League college. There was luck of course. And the reality of working his way through school. But that’s a hell of a lot of cultural capital and privilege to build up in two generations. The question I find myself asking in your story, is: where is the generational aspiration? To be honest, this was so instilled in me from a young age,-The inevitability that I would exceed the accomplishments of my parents-that I am constantly perplexed to encounter peers who were not expected to do the same. Who were not told that the past barriers were behind them & of course, of course they would move beyond the accomplishments of their parents. I don’t think this expectation is solely the province of generational wealth. And based on my father, it is clearly not confined to families with privilege.

Hearing your story I’m all the more admiring of all that you’ve done, but also trying to factor my own reality of generational uplift into the poor Artist narrative. Your story resonates as that of rural working class. And although I’m no expert, seems to me to reflect an aspect of whiteness-isolation-that might be at variance with the experience of that of ethnic communities infused with ideals (mythical or otherwise) of uplift. As a Black artist I can and do look to those cultural communities of practice, the elders who open doors, pull our coats, raise us up. If I had been, say, trying to play classical music, I would’ve had a different experience. But as I often tell my students, choosing the path of being a New York Jazz musician in the 1980s seemed like the closest thing to job security that my Black 24-year-old self could imagine. So how to explain the fact that I was all ready to take out loans to get my masters degree at University of Miami, but when I arrived, the head of the program called me in and asked if it was true that I had just graduated from Eastman. Upon saying yes, he told me that their previously hired GTA had bailed ,and since I went to Eastman, I must be qualified to take that gig. So voila, free grad school. So, luck? Right place right time? Or just another example of privilege accruing to those who already have it?

Since, as a University professor in the arts, I am still in the business of creating multiple pathways for young artists to realize their potential, and keep their art in their lives for their entire lives. And since student loans are the devil! I’m Interested to hear anything you have to say about new models, new ways of thinking or organizing resources that will let our kids soar far above what was possible for us.

In gratitude,

Darrell

Thanks for this series. This is one of those topics that the culture wars have turned people into such unsympathetic a-holes about. Even on the left few seem to be able to resist the punchline of say, an philosophy MA with crippling debt and few prospects. (I'm lucky I got my overpriced arts degree in the 90s when things weren't nearly as bleak.)