Thanks so much for all your kind notes about my last post, the radically subjective review of the Dave Holland New Quartet show in Santa Fe. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, please consider becoming one? I could use your support.

Bud Powell was born 100 years ago today! As Gary Giddins wrote, “[N]o other pianist, and precious few musicians in any age, speak to us with such electrifying intensity.” Yesterday Kevin Whitehead’s strong Fresh Air piece explored Bud’s musical brilliance.

When I told a colleague I might share the following excerpt on Substack, he said, “But you didn’t write anything about Bud Powell in your Wayne book.” That alone is reason to share it.

A better reason is that Wayne Shorter’s 1959 onstage and hotel room meetings with Bud Powell in Paris are fascinating and evocative. A younger artist’s encounters with a revered elder can reveal much about both of them.

Again, it’s 1959. This edition of the Jazz Messengers includes Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Jymie Merritt, Walter Davis Jr., and Wayne . . .

In Walked Bud, from Footprints: The Life and Work of Wayne Shorter

On November 14th, just four days after Wayne’s first recording session with the Messengers, the band went to Paris. It was Wayne’s first European tour, and his first trip abroad. The Messengers flew over in a Stratocruiser, occupying the plane’s cocktail lounge in the bubble space above the main cabin. The ten-hour trip flew by for the band as they drank liberal amounts of cognac and worked out some tunes.

It was a good time to be a Jazz Messenger in Paris. A year before, the group had a triumphal premiere at the Olympia Theatre. Following gigs at the more intimate Club St. Germain had further popularized the group’s soulful brand of hard bop. Though the French maintained a preference for decades-old Lester Young-styled balladry—a style near their native chanson—bop had become the default soundtrack for younger Parisians, and a literal one for New Wave film directors. In 1957, Miles Davis composed the soundtrack to Louis Malle’s inaugural new wave film, Elevator to the Gallows. In 1960, jazz’s frenetic, impressionistic sound would support the street scenes in Breathless, the first feature film by Jean-Luc Godard.

That autumn, Godard was shooting in the streets near the Messengers’ accommodation, the Hotel Cristal in the heart of St. Germain de Pres on 23 Rue St. Benoit. The Hotel Cristal was chosen primarily for its proximity to the Club St. Germain. “But Art always reminded us—he was always repeating important stuff—that the hotel had a rich history,” Wayne said. “It was where the black culturati stayed, like [jazz musician] Mary Lou Williams and writers like James Baldwin and Chester Himes.”

The Jazz Messengers’ November 15 concert in Paris, without Bud or other special guests

Their tour began in Paris at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees on November 15th, continued on a swing through Europe, and came full circle with a closing gig back at the Champs-Elysees on December 18th. For the final performance, promoters planned to feature a number of expatriate musicians in concert with the Messengers, including pianist Bud Powell, who’d set up residence on the Left Bank the previous May.

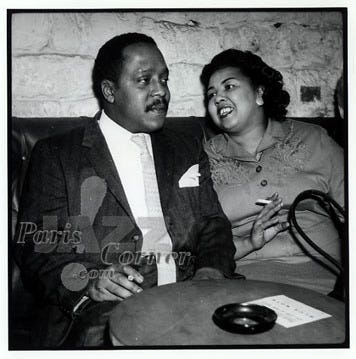

Bud was doing well in Paris. The French had romantic benevolence for Black American artists, and didn’t seem to care that performing had become a challenging high-wire act for the pianist. By the end of the 50s, the genius of bebop piano was as legendary for his instability as his music. These days Bud started sweating before he even sat down at the piano. Once his piano playing had raised a daringly imagined arch between the opposing poles of Art Tatum and Thelonious Monk. Now he was just walking the line, trying to keep his balance and see his way safely through to the other side, wherever that was, and finish the gig. Still, Bud was working a lot, thanks to his lady companion Buttercup and young fan and helpmeet Francis Paudras. They tag-teamed on the full-time job of steering Bud clear of bars and into clubs for his gigs.

Paudras invited Bud to the Messengers show that night, unaware that his friend was actually already on the bill. In the middle of the show, Walt Davis Jr., the Messengers’ pianist, stepped up the mic and asked Bud to come onstage. Bud wasn’t exactly eager to play. He sank down into his chair and vainly tried to use his trademark beret and overcoat for camouflage, but his fans picked him out right away. Paudras prodded him, the audience clamored, and finally Art enticed him onstage. “All I could think was, we’re playing with Bud Powell now, this is Bud Powell onstage,” Wayne said. “I was thinking of his music, and what he always played himself, and how to respond to that.” The Messengers honored their guest pianist by calling two of his tunes: “Bouncing with Bud” and “Dance of the Infidels.”

The Champs-Elysees audience caught Bud on a good night. With concentration, he shunned inspiration and played straight, giving a crowd-pleasing performance—though no matter how Bud played, he was bound to be the night’s sentimental favorite. More impressive musicianship may have come from the Messengers’ two horn players. Only a few months into Wayne’s tenure with the band, he and Lee Morgan had settled into the frontline as comfortably as an old married couple: they formed a striking contrast, a musical yin and yang.

Lee strutted across the stage with a bop walk, his lankiness and high-water pants lending the step a particular insouciance. His trumpet solos were as gutsy as they were virtuosic, with strong flashes of funk and blues. In contrast, Wayne’s stage demeanor was absolutely wooden. Messengers fans had begun calling him “The Sphinx”—his displays of emotion were so rare that his slightest smile had the impact of a man coming out of a coma. In his solos, Wayne effected subtle drama, with long, elliptical narratives that he developed with the slowness of a symphonic piece. Wayne’s studiousness complemented Lee’s expressiveness, establishing a formula that would play out again and again throughout Wayne’s career. He’d later be the studious straightman to the heart-melting trumpet of Miles Davis, and then to the provocative keyboards of Joe Zawinul in Weather Report. This equation played out in even more brief partnerships, when he foiled the expressionistic rock riffs of Carlos Santana.

After the show, the Messengers gathered backstage with Bud and their other guests. Bud’s tough-love warden-paramour Buttercup cornered each of the Messengers and warned them about Bud’s tactical disappearing acts. “Whatever you do, don’t let Bud out of your sight,” she said. “And don’t give him any money. He’ll use it for wine, or worse.” Buttercup was roundly ignored. The Messengers were focused on some friends from the States who had joined them backstage. Prizefighters Rocky Graziano and Sugar Ray Robinson, both Birdland regulars, were in Paris on a showbiz tour. The actress Hazel Scott was a newly free woman in Paris, having just left her husband Adam Clayton Powell, the first black congressman. According to Francis Paudras’ account in his memoirs, Buttercup was so affronted by the Messengers’ disregard that she retaliated by calling the police. Paudras claimed that Wayne was among a group of musicians who were taken to the police station, strip-searched and made to spend the night in jail. Paudras didn’t specify the exact nature of the crime that would have justified this quick rallying of the French forces.

As Wayne tells it, he was not among that group. He took a cab back to the Hotel Cristal from the Theatre. On this night, like the others, there were tempting reasons to stay out—adulating French girls and free-flowing vin rouge—but Wayne didn’t feel like warming himself at the fire of human companionship. He’d stay in his room, drink a bottle of wine on his own, and work on some tunes. Wayne had been writing for a couple of hours when he heard a knock on the door at around 3 a.m. He opened it, expecting to see Lee or Walter, flush with drink. Instead, Bud Powell stood there in his beret and overcoat, sensible enough attire for the damp December chill of Paris. But Bud wore this uniform year-round, even in the asphalt oven of Harlem in July. Mindful of Buttercup’s warnings, Wayne looked anxiously over at his night table, which held a mound of French francs. Bud didn’t seem to notice the money. He walked into the room, sat in a chair, and looked over at Wayne’s horn, which was out of its case on his bed. “Play me something,” he said, in his mild child’s voice.

Wayne hesitated. He didn’t know what to play. When he picked up his horn, he reflexively set in on one of the tunes they’d covered earlier that night, “Dance of the Infidels.” After a slow start with some nerve-rattled lines, Wayne relaxed into the tune, staying close to the melody but stretching the rhythm a little according to his own design. After he played, Bud thanked him, stood up, and walked to the door. He turned around and stared. “Are you alright?” Wayne asked. “Uh-huh, it’s all right,” Bud mumbled in response.

“Bud had that wild look,” Wayne remembered, “But it was contained. I knew about Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital and something–otomy and how they tried to shock him. But when he went down the hotel stairs that night he walked straight, with his hands in his pockets. He wasn’t wobbling, he wasn’t ripped or anything.” But if Bud wasn’t looking for a fix, Wayne didn’t know what to make of his late-night visitation. He vacillated between convincing himself it had been an apparition and puzzling over possible motives for the visit. Why him and not Lee? And why had Bud requested the solo concert? Wayne deposited the episode in his memory banks, though with time his interest in understanding its significance only grew.

Wayne related the story to director Bertrand Tavernier years later, in 1985, when he performed and acted in Tavernier’s film Round Midnight. Dexter Gordon played the film’s lead character, an expatriate American jazz musician in Paris who was a fictionalized composite of Bud Powell and Lester Young. The film was based on Francis Paudras’ memoir Dance of the Infidels, though Wayne hadn’t read the book and was unaware of Paudras’ conflicting version of that night’s events. Tavernier was altogether unconcerned with veracity and considered putting Wayne’s meeting with Bud in the movie. But a scene in which a lucid Bud Powell sought out new music from a younger player was not much in keeping with the film’s portrayal of him as a wine-crazed, talent-squandering character. Whether it was a practical or aesthetic choice, Tavernier ultimately decided not to include Wayne’s Hotel Cristal episode in the film. Musical director Herbie Hancock and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson are the musicians with the most significant acting roles in Round Midnight. Wayne’s main appearances are musical—he performs onstage at the Blue Note club and at a recording session. His one extra-musical appearance is in an atmospheric scene at the session, where he is briefly shown entertaining some fellow musicians with a story about his favorite movie, The Red Shoes.

Bud Powell’s daughter Celia was also on the set of Round Midnight. She was struck by Wayne’s story of her father’s appearance in his hotel room. “You all had played together and father was a guest with the band that night?” she asked him. “You know, father didn’t go up to see you to get money, he didn’t sneak and hide from people to see if he could find someone to help him get drunk. Father followed music, and he went to see you for the reason that he said. To make sure that everything was all right.” Wayne couldn’t imagine what she meant. “For the future of music,” she explained. “He heard something going on with you that night when you were playing.”

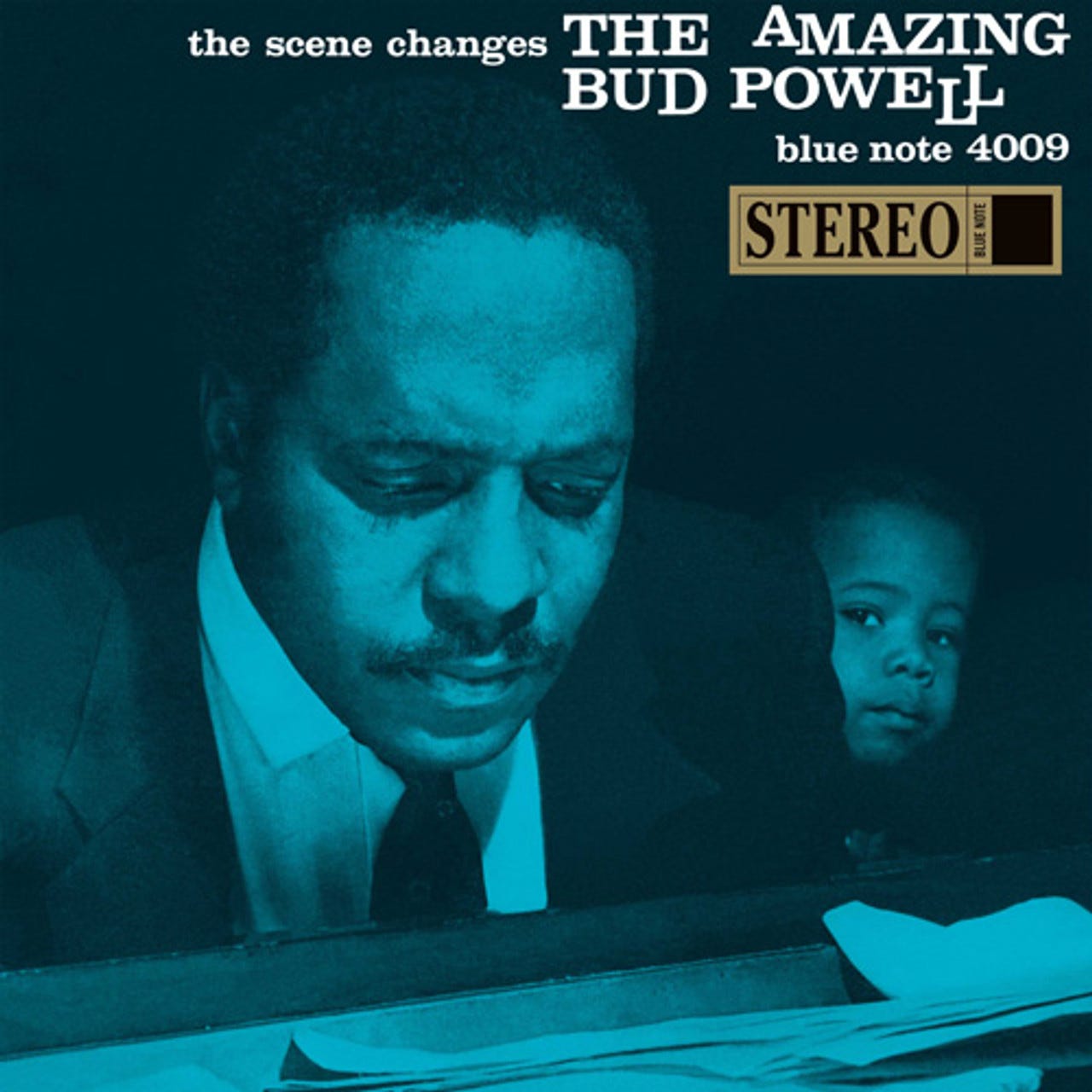

After talking to Celia, Wayne listened repeatedly to the show’s live recording, Paris Jam Session, which was originally released on Fontana and later reissued on CD by Verve Records. Such deep investigation of a record was extremely rare for Wayne. It was unnecessary—he’d usually commit music to memory after one or two listens. But this time he set the needle down on the record’s edge dozens of times, hoping to solve the puzzle of what Bud might have heard. “That night, Lee played good stuff,” Wayne said. “And Barney played very nice, but . . . “ Wayne trailed off. “Maybe he must have heard something with me that he felt in his inner being? Like he never detached himself from knowing where he had wanted to go with his music before he fell off.”

What might Bud Powell have heard in Wayne that night in 1959? On side two of the record, there’s really not much to hear. That side features two tunes that the Messengers played alone, without their guests. On “The Midget” and “A Night in Tunisia,” there was more than a little Coltrane in Wayne’s sound and style.

The record’s A side, on which Bud joined the Messengers for two of his own tunes, was more revealing: Wayne’s handling of Bud’s compositions got to the heart of the pianist’s musicianship. The rather cliched version of Bud’s story assumes that his brilliance was forever dimmed by tragic events early in his career, that police beatings and then shock treatments unleashed in him an innate potential for madness. And whatever Bud’s genetic predisposition, abuse of such severity could certainly trigger insanity in anyone. But Bud was resilient, and his career wasn’t so much a downward spiral as it was a seesaw between brilliance and incoherence. Maybe what perpetuated Bud’s mental illness was his frustration with being unable to realize his potential. Genius doesn’t guarantee madness, but the torture of frustrated genius does.

That night in Paris, Bud set out boldly on “Dance of the Infidels” with an inventive solo. He walked the tightrope for a few bars then fell back on repetition like a net. When Wayne took the lead solo on “Bouncing with Bud,” the next track on the record, Bud must have noticed that Wayne never repeated himself—not a single riff. For Wayne, repetition was stagnation. He simply couldn’t traverse old ground. More than that, Wayne’s playing reflected Bud’s in the way he pushed the tune’s melody away from its harmony, in the way he courted dissonance with the master plan of a classical European composer.

Wayne played like the Bud Powell of “The Glass Enclosure,” Bud’s 1953 masterpiece composition. The tune began as a fragment that producer Alfred Lion heard on a visit to Powell in the apartment where he was kept, and was titled in reference to that prison-like space. “See, Bud’s inside the glass enclosure,” Wayne said. “He’s breaking out with this tune, but in a subtle way. The music is right on the crossroads of classical and jazz. Like you can hear Shostakovich and Stravinsky doing that stuff, if you had the good fortune to hear either of those composers alone at the piano. You’re eavesdropping on their reverie. There you can hear where Bud might have gone.”

“The Glass Enclosure” certainly points to a talent for composition that was sadly underdeveloped. Like Wayne’s compositions, it has the sheer drama of a soundtrack, and unfolds like a narrative. Its chords are so dense that the notes seem to clench one another, but the breadth of their structure allows the sound to bleed away in opposite directions. Alone at the piano, Bud contained the instrumental scope of a symphony and bottled all the sprawling cruelty of The Rite of Spring. And though jazz musicians didn’t start playing Lydian augmented chords with any frequency until the 1960s, Bud Powell played a few on “The Glass Enclosure” in the early 50s.

In his penetrating analysis of Powell’s music, Gary Giddins concludes: “The reason we read more deeply into Powell than into many of his contemporaries may be quite simple: no other pianist, and precious few musicians in any age, speak to us with such electrifying intensity.” Wayne sometimes says, “Jazz for me is ‘Do you have the guts to do it?’” There was urgency in Wayne’s playing at the Theatre Champs-Elysees that night, an inner logic to his solos, but a mercurial aspect as well—Wayne blew back at Blakey’s high-hat jabs like they were in the boxing ring. The seeds of Wayne’s style and his initiation as a composer were there. Maybe Bud heard that, Wayne pushing toward the future with music that could only move forward.

(((❤️❤️)))

Just wow and thanks for this bit of history. I’ve always loved Bud Powell’s music, but never had a clue about who he was. This post brings life to “behind the scenes” creating such an amazing collaboration of musical minds.