Hello, everyone. My plan for early this week was to post about reading my way back to Los Angeles. I’ve been on a contemporary LA fiction deep dive to prepare for a housesitting and reporting stint in Hollywood’s Beachwood Canyon. My trip was set to begin this weekend.

We all know what happened next. On Tuesday, the Los Angeles wildfires erupted, with hurricane-force Santa Ana winds quickly propelling them out of control. Wildfire news always brings on a visceral sense of the Colorado fires I’ve experienced directly. Especially our 2012 Waldo Canyon wildfire. As with the current infernos in L.A., high winds whipped the Waldo Canyon fire into neighborhoods so quickly that the best firefighters could do was try to get everyone out of its way.

My heart goes out to Angelenos who’ve lost their homes and communities. Their grandparents’ wedding photo. Their kid’s elementary school. Their soup spoons. I sympathize with everyone who’s felt the profound unease of encroaching flames, even in relatively safe sections of the city. With everyone who’s trying not to breathe the toxic smoke that’s hanging around like existential dread. The word apocalyptic so often seems overwrought, but in the case of these LA fires is almost inadequate.

Meghan Daum’s brief narrative/commentary on losing her Altadena home made the catastrophe all the more real for me. She has an important perspective on the fires, especially for those of us who are watching the devastation from afar. Highly recommended.

I’ll cover contemporary Los Angeles literature when the great city has had a chance to recover. In the meantime, here are some thoughts on how a well-set novel can prime us for a more meaningful experience in a place we visit. Some of us may, at times, prefer to vacate workaday life on a pleasantly blank beach, relaxing on the surface of a place. But most of us want to be more present and perceptive when we’re out on the road, right? We want to be more there while traveling. Reading fiction brings us closer to places so effectively that it almost feels like cheating.

Key To The Kingdom: Reading into the human heart of a place

Remember consulting physical guidebooks for travel? Whenever I opened a new one, I’d skip past the photos and go directly to its section on literature or further reading. I wanted fiction recommendations for my destination.

Novels have long been my secret weapon in travel preparation, especially when I’m reporting overseas. A good novel provides a felt sense of a place, helping me absorb more practical geography, modern history, and cultural anthropology than a dozen guidebooks. Facts can be checked later. Going into a new place with a felt sense of its culture is golden.

Lately, I’ve noticed more recommendations to read fiction for travel. Last summer, for example, a Denver Post article asked, “Ready to try a fiction-fueled vacay? Here’s how it works: Pick a title from the list below, read it solo or with your book club, then follow our travel notes to immerse yourself in a real-life literary setting.” A fiction-fueled itinerary isn’t a bad way to organize a jaunt around our mountain state. Yet this article’s approach makes novels into glorified guidebooks.

Fiction can do much more for us when we travel. For me, reading a novel set in a destination is not only about visiting landmarks frequented by its characters. It’s about something less prescriptive and more mysterious: being more fully human in a place. This may sound pretentious. By now, though, regular readers probably expect us to fumble toward profundity here at Call & Response. It’s just how we’re wired.

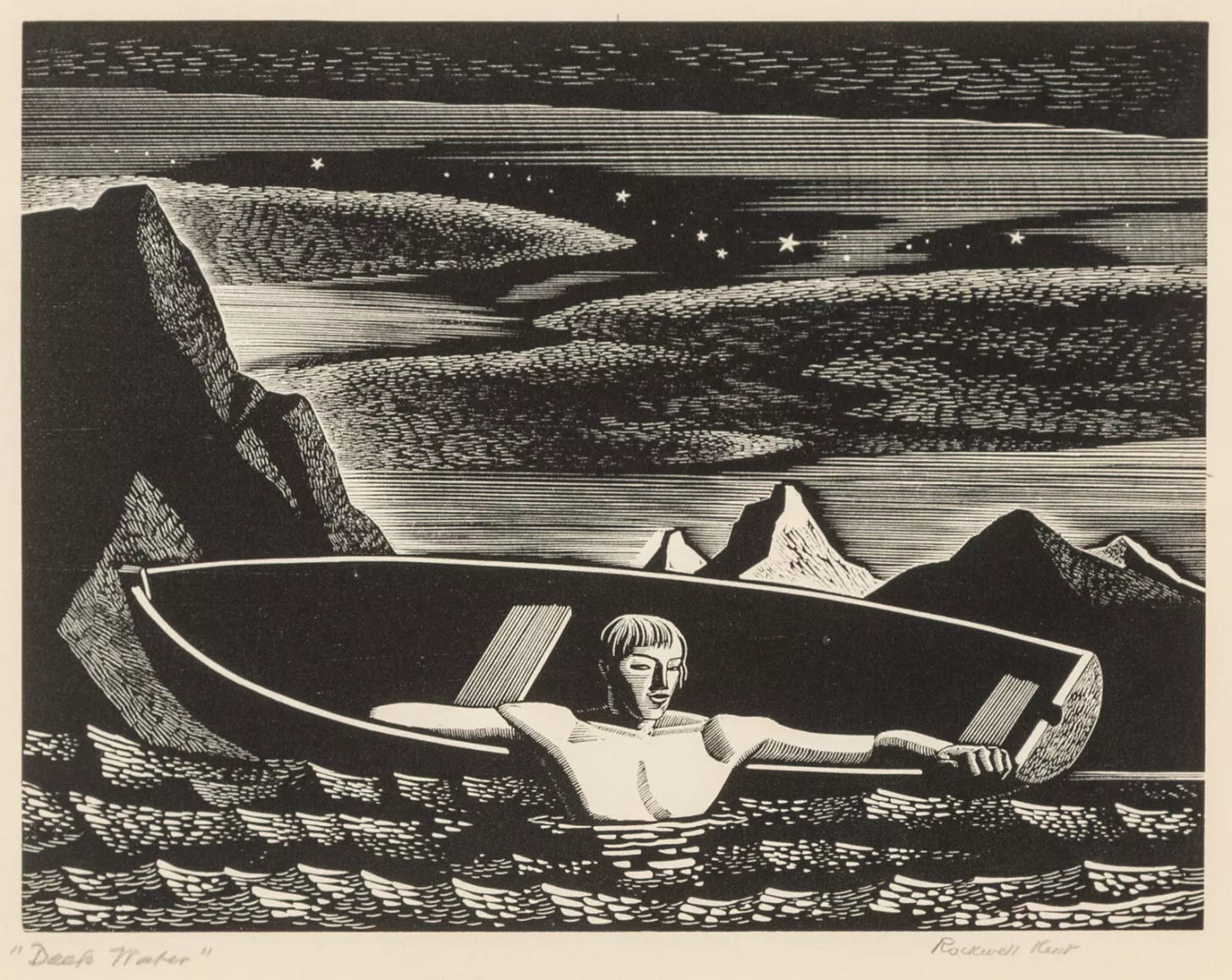

When I heard I’d been awarded a Newfoundland artist residency, Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News was as far as I’d read into the country’s fiction. I was in desperate need of edification. Among many strong Newfoundland book recommendations was Michael Winter’s The Big Why, a novel about real-life American painter Rockwell Kent’s 1914 relocation to Newfoundland from New York. This visiting artist’s story intrigued me since I’d be a visiting writer there myself. Once I’d started the novel, the protagonist-artist’s voice kept me reading. Kent’s descriptions and reflections were ornery and deft, the perspective of an outsider struggling to feel his way into close-knit community. The novel offered a vivid portrait of Newfoundland and its inhabitants, all refracted through the flawed protagonist’s inner life.

After my husband and I settled into the Newfoundland residency last summer, we drove around to get our bearings. I spotted a road sign for Brigus.

“Brigus is the name of the town in that artist novel I read,” I told my husband. “I didn’t even know it was real.”

Driving through this real place, we saw a notice for Brigus Tunnel.

“That was in The Big Why, too!” I said.

The Big Why was far more faithful to its setting and truer to Kent’s life than I’d imagined. Along with the tunnel, I ran into a dozen of the novel’s other landmarks, even a charming old cottage on the steep hill where the artist actually stayed.

Visiting these places I’d read about was fun enough. What meant more on the ground, though, was the novel’s insight into local ways of thinking and being. For example, observing tiny windows on older Brigus homes brought back a moment in The Big Why when Rockwell Kent wonders why houses don’t provide more generous views of the bay. Why would we want to look at salt water when we’re out on it all day long, a local tells him. Of course. A century ago, this fishing community spent so much time struggling through icy water that its people couldn’t stand to lay eyes on the sea after they went home. (Also, I’d guess smaller windows fared better in lashing storms)

It’s human nature to relate to characters in stories. I don’t read well-set fiction so that I can become its characters when I go somewhere, but so those characters can walk alongside me there, enhancing my understanding of the local culture.

It wasn’t until news broke of a missing Newfoundland fishing vessel that I felt the real value of having read The Big Why. I heard about the missing Elite Navigator vessel in a Brigus pub, where it was an urgent topic of conversation. The Coast Guard launched a search with four ships, a helicopter, and a plane based on the vessel’s last-known position. Fog was heavy, though. I asked about their chances of finding the lost fishermen.

“We’ll see,” a bartender told me. “People die out there on the water.”

People die out there on the water. With a gut punch, I remembered The Big Why’s affecting account of The Great Sealing Disaster of 1914. 251 sealers died in two simultaneous disasters involving the SS Newfoundland and the SS Southern Cross. Many of the sealers were from Brigus.

The Elite Navigator crew had a happier ending last summer. The Coast Guard spotted a red flare and found all seven crew members in a life raft, where they’d floated for days after a fire took down their ship. Balloons, a flotilla of fishing boats, and a parade greeted the seven fishermen upon their safe arrival to shore. I celebrated with the Newfoundlanders. That this drama could have ended differently, and so often had, was something I felt in my bones, thanks to having read The Big Why’s rendering of tragedy at sea.

A novel’s slow unfolding can condition us for a richer experience on the road. Reading fiction is the opposite of rushing to the next site or sight. Fiction’s sustained revelation resists the browsing nature of modern life, training me to slow down and use all my senses to be somewhere long enough for it to open up to me. At least a little.

Along with a better travel experience, empathy is the goal. I keep seeing social media posts that deem the current California wildfire losses unfathomable. But long before I’d endured a wildfire myself, Joan Didion’s writing gave me a felt sense of them. She made me fathom them. Meghan Daum and other writers are already making the sorrow and stoicism of this new fire-ravaged LA comprehensible to us through narrative podcasts and essays. Novels will come later.

Why read well-crafted narratives set in places we visit or may visit one day? Because great literature equips us to stand with our fellow humans through pleasure and pain, dread and joy. It allows us to be with them, right there in the place they live.

.

Thank you