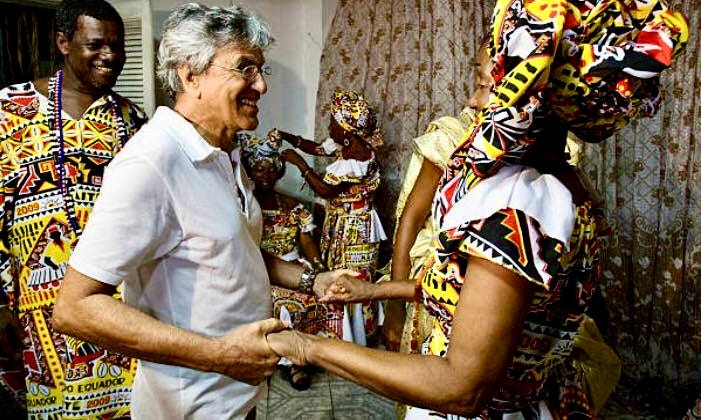

This post is special. In 2002 I made my first reporting trip to Brazil, including a couple weeks in Salvador da Bahia, where I spent some time with Caetano Veloso at carnaval. This longform reported essay examines Bahian carnaval culture, Caetano’s role in it, and the overseas reporting process itself. The piece closes at Caetano’s home with my favorite scene I’ve ever experienced with an artist. Please enjoy.

A hard-falling rain sent rivulets of water down the steep street. Splattering onto tin roofs and cars, the raindrops seemed to beat in time with the caixas, or snare drums, in front of me. The sound of pounding rain was absorbed into the booming bass drums behind me. I adjusted my recorder’s levels, but there was no ideal setting for recording inside a rhythm explosion.

I was somewhere in the middle-back of two hundred drummers who were crammed into a side street of the Liberdade neighborhood in Salvador, Bahia. It was the group Ile Aiye’s kick-off ceremony to its carnaval parade march, which would take the percussionists ten miles into the center of town.

A few rows ahead, a drum leader whistled two short blasts, and a new rhythm spread back through the rows of drummers, its split-second delay from row to row reminding me of a flock of birds changing direction. After the new rhythm had taken hold, the leader held up two fingers, and eight bars later, the music stopped. From inside the group, rhythm’s abrupt halt felt like thunder silenced mid-peal. The rain kept falling.

Up on a nearby balcony sat Ile Aiye’s elder women in lacy white baiana dresses and turbans. From the balcony they threw ceremonial foods, hominy and popcorn, or pipoca, which also is the name for the energized bouncing of the carnaval crowd.

A trumpet fanfare blasted from the top balcony of the house. Ile Aiye's leaders and pop star Caetano Veloso released doves into the air.

To put this moment in some perspective, seeing Caetano—everyone in Brazil calls even the most famous stars by their first names—holding court with the elders of Ile Aiye, was, for an ardent fan of Brazilian music, like seeing Muhammad at Mecca. Caetano is one of Brazil’s most popular and influential singer-songwriters, often referred to as the Bob Dylan of Brazil. It was with Caetano’s song “Ile Aiye” that many Americans, including me, first heard of the group. The song was included on the 1989 Beleza Tropical recording compiled and released in the United States by David Byrne.

"Um Canto De Afoxé Para O Bloco De Ilê (Ilê Ayê)” by Caetano Veloso, from Brazil Classics 1: Beleza Tropical compiled by David Byrne

I’d been hanging around Caetano at the 2002 carnaval for a few days, per arrangements we’d made back in New York, where I lived. The idea, dreamed up with my National Public Radio producer, was that I’d follow Caetano with a microphone while he commented on the carnaval proceedings for a radio story. Although Caetano and I had enjoyed some friendly banter, somehow it always felt wrong to shove a mic in his face, taking him out of the moment with an interview. In the meantime, I was immersed in carnaval culture and music, not a bad thing for my reportage or general happiness.

The percussion resumed, and with it dancing by both the Black locals of Liberdade and the lighter-skinned Brazilians and tourists who’d come inland from oceanfront neighborhoods. Brazil’s dancing culture was far less judgmental than most. Even an awkward gringo could disappear into the anonymity of this pulsing collective—that is until he found his unique groove. Whatever that distinctive groove was—the hustle, a self-styled samba, hip hop krumping, or a dance move with no name or precedent—the surrounding crowd often recognized the gesture, parting to give props to the dancer. It was not unusual for lifetime non-dancers to convert when they visited Brazil, because dancing there was the best of two worlds: assimilation into the dancing masses or affirmation of personal self-expression.

Dancing light-skinned crowds at Ile Aiye’s parade launch testified to the advancement of Afro-Brazilian culture in Bahia. Ile Ayê was founded in 1974 as the first bloco afro, or Afrocentric carnaval club. In the beginning, Ile Aiye’s black percussion parades elicited mostly impatience from carnaval crowds, who wanted songs played by the trios electricos. Trios electricos are trucks equipped with powerful sound systems that carry performing musicians. They’re the emblems of Salvador’s carnaval. The tradition began in 1950 when two Bahian musicians, Dodo and Osmar, played with their electric trio aboard a rented 1929 Ford Model T. Over the decades, trios electricos evolved into big tractor-trailers with platforms holding dozens of band members and dancers. “Like Las Vegas on trucks!” as Caetano described it to me.

It was with its music that Ile Aiye won the hearts of the carnaval crowd. That music was a blend of samba and reggae, a stylistic homage to black-pride icon Bob Marley, combined with the older Bahian variety of samba called samba de roda.

After Ile Aiye came other blocos afros, including Olodum, for which the term “samba-reggae” was first used. Olodum managed a popular breakthrough for all blocos afros in 1987 when its song “Farao” became a carnaval hit. By the early aughts, samba-reggae was the most common musical style in Salvador, a lingua franca for blocos afros and trios electricos alike.

“Cerca De Bakel,” Ile Aiye

Membership in Ilê Aiyê had always been limited to “Black Brazilians of African descent.” The issue of race in Brazil can be confounding to someone from the U.S. The country didn’t have America’s one-drop rule or concomitant laws condemning anyone with even a hint of African blood, so intermarriage was more common in Brazil than in the United States. Nearly 80 percent of Salvador’s residents identify as black or mixed race. Some Brazilians will tell you that “miscegenation” always has been a positive practice in their country.

In the 1930s, Brazilian anthropologist Gilberto Freyre introduced the idea of a "Brazilian racial democracy,” arguing that racial mixing in Brazil enriched and empowered the culture. Freyre’s theory of mulatto superiority caught on so well that many Brazilians came to see their country as a discrimination-free zone. It’s usually lighter-skinned Brazilians who take this view, which can seem a consensual hallucination in a place where racial inequality is so glaringly obvious, where so many of the wealthy are white and the poor black. Racial inequality certainly was obvious to the founders of Ile Aiye, who saw the need for a separatist, black pride group.

There at Ile Aiye’s parade launch, I looked up to see Caetano Veloso pointing at me and smiling. Caetano’s signal probably meant he wished he could cast off his elevated status and be down with me among the drummers. At any rate, it was time to give myself over to the pounding present. I put away my microphone and recorder, closed my eyes, and let the feeling of the rain merge with the sound of the drums.

I could talk to Caetano after carnaval. Trying to talk during the festivities was a bad idea, as impossible as asking Babe Ruth to discuss a game as he played at Yankee Stadium or a priest to comment on mass while he offered it. From the inside, this party was too sacred and fun for words.

Compared to Rio’s carnaval, Salvador da Bahia’s event was a relatively democratic affair. In Rio, people spent thousands on seats in the Sambodromo stadium to observe samba school dancers shimmying in elaborate costumes, for which many saved all year long. Bahia’s (Brazilians refer to the city this way) carnaval was considered more authentic, partly because its division between performer and spectator was not as distinct: Civilians helped create much of Bahia’s carnaval on the street itself.

Bahia’s carnaval did have its socioeconomic stratification. My assignment to interview Caetano landed me in the glamorous camarote, or balcony party, of musician Gilberto Gil, Caetano’s lifelong friend and collaborator. The cost was 90 USD a night, prohibitive for all but the wealthiest Brazilians. Gil’s camarote was located at the start of the major parade circuit that took trios electricos miles along a coastal avenue. Two floors of balconies gave Gil’s partygoers stage-level views of truck-topping bands as they started the parade with short musical sets. Quincy Jones, Bono, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Naomi Campbell, Ziggy Marley, Queen Silvia of Sweden, and numerous Brazilian VIPs have been visitors to Gil’s carnaval hang over the years.

Across the street, a lighthouse stood guard over a fort, with trails leading to grassy seaside perches beyond. One carnaval night, I ducked and wove through the hopping sidewalk throngs and walked behind the lighthouse to discover several couples tangled on the grass in flagrante delicto.

On the street some partiers could grow agitated and punchy, an effect of the then-trendy pastime of huffing fumes from glue-soaked rags. Pickpockets were common. Up in Gil’s camarote, the most dangerous activity I witnessed was some models snorting cocaine off each other’s cleavage in the bathroom. Down on the street, police didn’t always take the time to discern between the playful fights of capoeiristas, or marital artists, and the deadly conflicts of bona fide street thugs. Guiltless people could find themselves arrested before they knew what had hit them. In contrast, a camarote gave attendees the protections of the social elite.

Another popular alternative was paying to follow one of the rolling trios electricos. Bands on trios electricos charged revelers upwards of hundreds of dollars for the privilege of modeling their T-shirts and dancing inside cordoned-off areas around their moving trucks. A well-known band could make six figures over carnaval’s four days.

It wasn’t always that way. In "Atrás do trio elétrico,” Caetano Veloso's 1969 homage to carnaval, he sang, "Átrás do trio elétrico só não vai quem já morreu,” or “Behind the trio elétrico only the dead don't follow.” Back then the trios electricos were open and free. By the 1990s, when trios had begun charging admission, critics were parodying Caetano’s song with the cynical remark, “Behind the trio elétrico only those who have paid can follow.” The harshest critics claimed Salvador’s previously classless carnaval was thoroughly ruined by these “roving country clubs.” Some Salvador residents left town each year for relatively small, homespun carnavals up the coast in Recife and Olinda.

Gil’s camarote was filled with perks, starting with a bounty of catered food. On a balcony, head wrapped Baianas served the popular local snack of acaraje, fried bean fritters topped with hot peppers and dried shrimp. An atrium held a boatload of sushi, literally, with raw fish covering the deck of a 10 x 4 sailboat. A big crowd gathered before a commercial-size oven where fresh, steaming batches of pao de queijo, or cheese bread, appeared every 20 minutes or so. Also in the camarote were an open bar, a fortune teller, a dance floor, and a private chill-out room, which tended to be occupied by children.

For the third time since I’d arrived that night, a DJ played Brazilian superstar Ivete Sangalo’s “Festa,” an unambiguous song about a big party that had started in the ghetto. It was the hit of 2002 carnaval, though the song’s popularity was a source of controversy. Traditionally, carnaval tunes were performed by blocos throughout the four-day event, with the most popular tune emerging on the strength of the crowd’s reaction. On my 30-hour bus ride from Rio, fellow passengers produced guitars and played some of the top carnaval song contenders. But Ivete Sangale had released “Festa” on an album in 2001, so it had been circulating on the airwaves for a year, giving the song what carnaval hard-liners considered an unfair advantage.

Out on the dance floor were some sleek women who didn’t seem conflicted as they sang and bounced to “Festa” in their hand-made variations on the camarote party’s special t-shirt. Some t-shirts were lightly ornamented with frills, lace, and buttons; some were cut down into revealing halters. Wearing the camarote t-shirt proclaimed one’s membership at the party. Adapting it advertised one’s creativity and individuality.

Beside the dance floor, I found Caetano’s manager Gilda Mattoso, my main contact in town, and told her an interview with Caetano during carnaval was all wrong.

“You figured this out?” she teased. “Sure, you can sit down to really talk with him when it’s over.”

Renowned enough as a musician manager that she went by her first name alone, Gilda also happened to be a famous widow, the last of Vinicius de Moraes’s nine wives. Vinicius, the playwright of Black Orpheus and lyricist for dozens of bossa nova classics, including, yes, “The Girl from Ipanema,” was a bohemian public intellectual and notorious womanizer. 41 years Vinicius’s junior, Gilda was married to him only two years before his death in 1980, but that brief bond seemed to provide her with enough romance for a lifetime. Once, when I asked if she’d ever remarried, Gilda replied, “After Vinicius, why?”

“I’m concerned that you are not dancing enough,” Gilda said to me as she accepted a cocktail from a passing waiter. She walked away, probably in search of more amusing carnaval company. Back in New York the press clung to the sidelines at shows, broadcasting objectivity with their distance from the action. In Bahia, partying seemed to enhance professional reputations.

Around midnight Caetano entered the camarote, and as on previous nights, a steady stream of admirers approached him. An old friend from high school had a niece who was dying to meet him. The president of Salvador’s Modern Art Museum wanted to say hello. And so on. Caetano offered little more than polite nods, exhausted after performing on top of a trio electico, keeping the crowds popping for several hours.

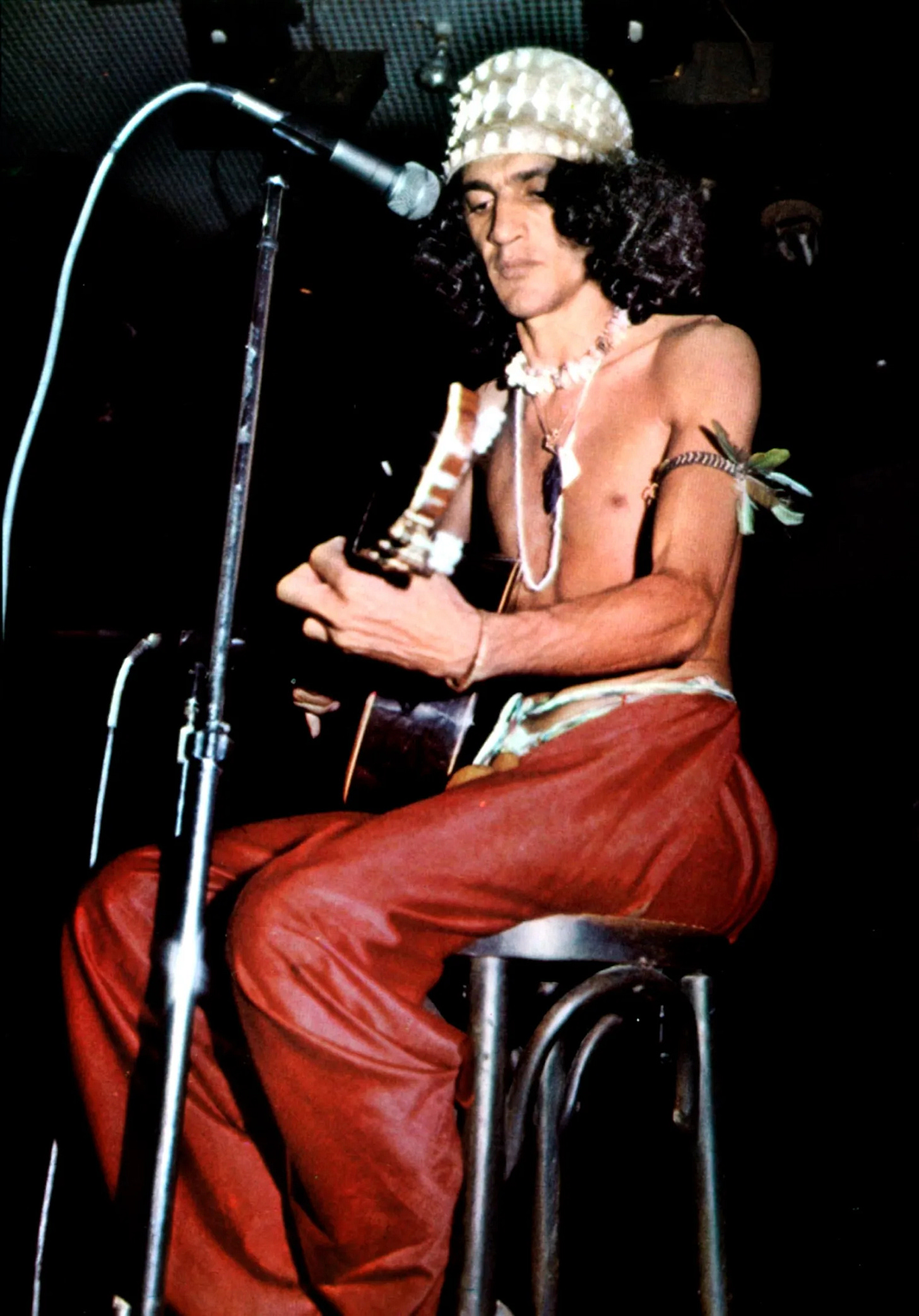

The cult of celebrity around Caetano could be extreme, but he’d come by his fame honestly, through artistic invention. In Rio’s Museum of Image and Sound, I’d watched a video of a 1963 Joao Gilberto concert, the great bossa nova pioneer whisper-singing in a complex rhythmic relationship to his densely strummed guitar. In this video, the camera pans the audience, and there in the front row sit a couple of quietly beaming 20-year-olds, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. Caetano began his career as a Joao Gilberto imitator, as evidenced by Caetano’s first studio session, Domingo, recorded in 1967. Just as jazz singers are bound to traffic in the tradition of Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughn, all Brazilian ballad singers have to negotiate the bossa nova legacy, one way or another.

On his 1989 album Estrangeiro, however, Caetano sang, “Some may like a soft Brazilian singer / but I’ve given up all attempts at perfection.” This lyric alluded to some serious personal and artistic history. Not long after Caetano’s career launch, he started listening to the Beatles’ experiments and dropped soothing bossa nova for more confrontational hybrid pop music. He joined the “Tropicalia” revolution with songs of protest against both Brazil’s military dictatorship and prevailing musical style. This aesthetic shift played a role in Caetano and Gilberto Gil’s 1968 arrest, incarceration, and two-year exile to London.

Though their exile to chilly gray England was tragic, it wasn’t all suffering in swinging London for two twenty-something musicians with an avid interest in the counterculture. This time in exile certainly deepened Caetano’s dedication to his native music, though for him, dedication meant taking traditional songs and turning them inside out with surreal lyrics and erudite harmonies. Brazilian artists’ general disregard for artistic purity and stylistic “cannibalism” today owes something to Caetano and other tropicalistas’ refusal to hold anything in music sacred, even under brutal military rule.

At the camarote party, Caetano slipped away from his thronging admirers and into the chill-out room. I reported on the party as a participant observer until 3 a.m., when it was still hours from ending. Happily exhausted, I slid into a taxi.

“Alegria!” the cab driver said, gesturing to my face. I took it as a compliment. The word means “joy” in Spanish. In Brazil, alegria can mean something a little more, a joyful surrender to the pleasures of the moment.

A couple of days after carnaval, I took another taxi, this time to Caetano’s seaside home in the upscale neighborhood of Rio Vermelho. With me was the translator Caetano had requested but wouldn’t need. When we rang the bell, a maid appeared and told us Caetano wasn’t home yet. She offered fresh juice and guided us out to a deck with a broad view of the gleaming blue bay.

Nearby a man lay in a hammock strumming a guitar while seeming to doze at the same time, as if there were a conspiracy to stage the scene a visitor from overseas would most expect to see. Other beautiful people swung by, introducing themselves as Caetano’s friends and family.

We waited. Long enough for the tide to go out, exposing rocky shoreline pools.

“The city of Salvador just named all those rocky tidal pools after Greek Gods,” I lied to the translator, pointing down at the shoreline. “In Caetano’s honor.”

“No, really?” the translator asked.

“Yes, that’s how special he is around here,” I went on. “See that one? It’s called Aphrodite’s footbath. I saw these on a tourist map. That big one over there is Zeus’s wading pool.”

“And over there is the finger bowl of Adonis!” Caetano spoke from the doorway behind us. He’d been eavesdropping on my joking riff and was more than ready to join in.

“Actually, the city would of course name the pools after Orixas,” he added, referring to the gods of candomble, the Afro-Brazilian religion. That’s where he’d been, at a candomble ceremony, Caetano explained, waving at his all-white attire. This excused his lateness, because at a candomble ceremony one chants and sings until the spirits come. Caetano had kept us waiting because the gods had kept him waiting.

“I saw you, Michelle, at the Ile Aiye parade, in the rain,” he said, in English that was accented Portuguese, of course, but also slightly British, an effect of those years in exile. “You were christened? Baptised.”

“When I saw you I was thinking of my own rainy reinitation to carnaval in 1972,” he went on. “I had been in exile for two and a half years in London. I had written some frevos [a type of carnival march with fast syncopation] for the trios electricos, or carnival floats, to play at carnival, but in London I was never able to see people jumping and singing my own frevos. Finally I was allowed to come back.”

“When carnival came I went out with my father and mother and sisters and brother and my wife to see the trios parade. And as a surprise, I saw this trio electrico rolling down the street in the form of a spaceship. And it was very magical because the frevo they played was my song, “Rain, Sweat and Beer.” When they started playing it, a big rain started and it rained the whole night through. And nobody went back home. Everybody was singing a song of mine about the rain, in the rain. I was really crying, you know. And as it approached I could read the name that they put on top of the spaceship and it was ‘Caetonave.’ It was a pun on my name with the word ‘ship.’ So it was very touching.”

It was a moment when the world manifested as Caetano’s very own poem, which seemed to be his ideal state of affairs. His lyrical speaking style made his conversation feel musical. As he and I talked, the benefit of having waited to talk until after carnaval became clear: I’d absorbed enough of the festival’s culture for us to have a real discussion. Caetano provided valuable context. When I said that corporate sponsorship seemed to have invaded the event, he reminded me that logos were a part of the very first carnival, which was sponsored by a beverage company. I suggested in the U.S. artists sometimes make hybrids for novelty alone, and the effect of putting bluegrass and tango, for example, could be brainy. But in Brazil, on the other hand, artistic collages seemed more organic, evolving in the service of expression. Why was that? Caetano’s answer surprised me.

“We are a huge country in the Southern Hemisphere and we don’t speak Spanish. We speak Portuguese, because we were colonized by another country. We are the biggest black population outside of the African continent. All of this is a disadvantage and puts us in a curious situation. We are kind of easily tilted by any foreign or international movement, or wind, or whatever. For lots of Brazilians, any one element of Brazilian culture isn’t anything to be proud of. And a symptom of this is that we created this ideology of cultural cannibalism. So you have this humble, kind of depressed way of seeing Brazil by Brazilians, this inferiority complex. It has helped to give birth to an idea that because we are nothing, we can take anything and transform it into a new thing that can walk with its own legs.”

Brazil’s sophisticated hybridity in the arts emerged from a national sense of insecurity? The theory was weirdly psychological but worth considering. What about the country’s racial contradictions? I was most interested in hearing from one of Brazil’s leading artists on that matter. How about the common claim that there was no racism in Brasil, and then the need for a separatist group like the carnival bloco Ile Aiye?

“Ile Aiye was conscious of the fact that in Brazil racial criteria were never seen as valuable. We were naturally color-blind and that was good, but this also helped bad things continue. You know the horrible statistics about dark skinned people in Brazil - the reduced social and economic opportunities they have compared to we lighter ones. So Ile Aiye was influenced by the black power movement that was very strong in the U.S. and in South Africa. Ile Aiye took on their own skins as part of their costumes for carnaval. Their fancy clothes would start with their own skins, so you had to be black to join them. It’s very interesting and convoluted, because they are the only separatist group in Bahia. It’s really a rare case in Brazil to have any racial restrictions. The more politically radical blocos never made the decision to forbid white people to join in. Ile Aiye is not so politically radical, they have more of a center-right political position. That makes Ile Aiye’s separatism kind of sweet, actually. There’s always this strange Brazilian balance around the racial issue, or question or problem.”

This answer, for all its vagueness, explained a lot to me. Caetano, who enjoys something like Susan Sontag’s intellectual status in Brazil, loves to articulate his country’s paradoxes. In fact, as an answer to my question about a racial contradiction, he took refuge in . . . contradiction. I wondered about this “we can have it more than one way here” attitude in Brazil. This worldview seemed great for art—the stylistic “cannibalism” of the country’s music testified to that—but bad for solving problems of social inequality.

“Os Passistas,” Caetano Veloso, Livro

After the interview, Caetano guided us to a courtyard lush with mango trees and bougainvillea vines. I thanked him for his time and insight. In response, he put a hand on my shoulder and began singing. “Meeeee-chelle, ma belle . . . “

I’d heard the Beatles’ “Michelle” more than a few times before, but Caetano’s rendition felt surreal. My translator grasped my elbow, whether in his own rapture or as a preventative to my fainting, I’m not sure. It was an enchanting moment, standing in a lush courtyard while Caetano regaled me with a songbook classic in a soft, bright voice that suggested, I have to say, nothing less than starlight.

But there was another dreamlike aspect to the scene. It had the imaginary quality of a movie set, an ongoing production in which Caetano felt obliged to play the role of silver-throated crooner, a character so charmed that it had somehow become his duty to charm everyone else. Fame was always pulling him toward his public image. And despite his complex history with the bossa nova tradition, Caetano did indulge its naïve sound, creating resonant tones that hung in the air like fruit just out of reach.

He thrived on carnaval performances because there he performed for crowds that appreciated him for intensity and endurance, his ability to keep people moving, not for his iconic image of sensual thinker with guitar. Caetano needed carnaval’s release as much as anyone in Bahia, probably more.

A loud sound interrupted Caetano’s courtyard performance of “Michelle.” It was a blunt thwack, as if a large bird had flown into a glass office building. Half a beat later came a toddler’s crying.

We looked over to see a red-faced little girl on her knees before a low window, howling and holding her forehead. The window rose from ground level to about three feet, and might have looked like a doorway to someone her size. Adults rushed to pick her up, soothe her. She must have hit the glass headfirst, they reasoned.

She seemed okay. While people wove a thicket of concern around the girl, I slipped behind them to the window. That impact had made quite a noise. I squatted and tapped on it hesitantly. How hard had the child hit the glass?

A pair of white-panted legs and handmade sandals appeared next to me.

“It was harder,” Caetano said. “She hit the window harder.”

“I know,” I said. “I just can’t seem to replicate. . .”

“Hit it with the tips of your fingers, like you’re playing a tabla drum,” he said.

That didn’t work.

“No, try the palm of your hand!” he commanded, leaning over.

I tried again.

“That’s not it,” he decreed.

“Why don’t you do it, Caetano?”

He squatted, cupped his right hand, and struck the window with both his lower palm and fingertips. A blunt smack sounded, exactly the one we’d heard before.

“That’s it!” I yelled.

“Yes, a true reproduction!” Caetano cried in triumph.

We became aware of another sound: silence. Everyone was staring at Caetano and me. My face fell as I registered their disapproval. You art monsters, you heathen aesthetes, their stares chastened, playing percussion on a window when a little girl has been hurt.

Caetano shrugged, but unlike me, couldn’t be bothered to look sheepish. The toddler, having lost the attention of her audience, stopped crying. Along with the others, she stared at Caetano, but her gaze was not judgmental. She was fascinated. Caetano smiled at the little girl and hit the window again, certain as anything that she would smile back.

Thanks for reading. I can’t forget to cite Why Is This Country Dancing? by John Krich as a book that prepped me on Brazilian music and culture before this first trip. Also, Caetano’s own book, Tropical Truth: A Story of Music and Revolution in Brazil, is a great way to go deeper.

Beautiful, Michelle!