“Which U.S. folk or pop songs are in three?” I wondered on the boat ride home from the island. “What song could bring Americans together in the same way?”

In May 2022, on my first post-pandemic trip overseas, I took a boat trip from Bergen, Norway to a tiny island. The official occasion was a floating celebration of the Nattjazz festival’s 50th anniversary. The true occasion was humanity once again crowding together unmasked on a pleasure cruise, gliding toward the watery horizon.

After we’d moored on the rocky island of Oksen, Hardanger fiddle player Nils Økland and harmonium player Sigbjørn Apeland treated us to some meditative folk music of exalted virtuosity, or what I think of as Norwegian soul music. The feeling was one of drifting into an atmospheric album cover, arriving at a place where landscape and music had merged.

Midway through their set, Okland and Apeland began playing a folk tune in 6/8 time, and spontaneously the crowd broke into song. In the way someone hearing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” doesn’t need to understand its lyrics to feel a swaying boat, this Norwegian folk tune suggested a ship at sea to me.

My iPhone video excerpt of the Nattjazz crowd singing “Vem kan segla förutan vind” certainly doesn’t capture the moment, but documents it at least. For your reference.

This singalong tune, I’d later learn, was the centuries-old “Vem kan segla förutan vind,” a sailor’s lament hailing from the Aland islands between Sweden and Finland. Generations of Scandinavian children sang it at school and home, sometimes as a canon, or in the round. “Vem kan segla förutan vind,” I was told, is also commonly sung at funerals and memorials. Together the song’s figurative and rhetorical lyrics, searching minor melody, and swaying rhythm convey the fleeting nature of human connection.

Who can sail without a wind?

Who can row without oars?

Who can leave a parting friend

Without shedding tears?I can sail without the wind,

I can row without oars,

But I can’t leave a parting friend

Without shedding tears.

Out there on the edge of the North Sea, the song allowed our group to sway, sing, and dream itself fully into the present while also grieving the pandemic’s losses.

This is what music can do, I found myself thinking. This is music’s power and meaning.

It was only with its 6/8 meter that this song expressed the moment’s mood so eloquently. “In three” is how musicians refer to any music played with a triplet feel, including 3/4, 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8 time signatures.

We may not think much about meter in music, yet we feel and react to it all the time. Eurhythmics, a pedagogy for interpreting rhythm with bodily movement (yes, Annie Lennox studied it as a child), helps kids work with their natural feel for music. We all have this natural feel: Three in music is swaying, rocking and rolling, spinning, spiraling, connecting, and lifting.

Which U.S. folk or pop songs are in three? I wondered on the boat ride home from the island. What song could bring Americans together in the same way?

3/4 and 6/8 certainly aren’t odd time signatures, like 5/4 or 17/8, e.g. Triple meters are so easy and conventional that we rarely even point them out. Still, they’re far less common than 4/4, or what we call common time.

A few months ago I bought my son a guitar/piano songbook, Songs of the 2010s: The New Decade Series, for sight-reading practice. Out of curiosity, I did the math, and made a count. In this songbook of 2010s pop hits, five of 68 songs are in 3/4 or 6/8 time. Only seven percent of the songs are in three, or about one in 14. The rest are in 4/4 or common time.

Why aren’t more songs in three?

The Holy Trinity and the Unstoppable Waltz

Time signatures go back, like many things in Western music, to the church. With the start of metered music in the late middle ages, almost all pieces used triple time. A 3/4 meter allegorized or represented the perfection of the holy trinity: the father, son, and holy ghost. Trinity time.

A new-to-me fact: The C that is now printed on scores to signify common time (4/4) was actually a broken circle meaning imperfect time. A full circle on the score once indicated perfect time, which is now represented as 3/4. Like God, tempus perfectum was seen as having no beginning or end.

Contemporary U.S. pop music in triple meters goes back to the waltz. “Waltz” comes from waltzen, German for “to revolve.” With its own roots reaching into the 16th century, at least, this Viennese ballroom dance journeyed far and wide in the late 18th and 19th centuries, adopting stylistic variations in new countries and cultures. You know the phrase, “Oh, you think you’re gonna just waltz in here and. . .” That’s basically what the waltz did. Nearly all partner dances owe their origin to the waltz.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the waltz was established in the U.S. The prolific early songwriter Stephen Foster wrote many waltzes or “parlor songs” in triple meter. A favorite of mine is the 1862 “Why, No One To Love,” performed by Judith Edelman on the 2004 Stephen Foster tribute album, Beautiful Dreamer.

NB: This is as good a time as any to note that triple meters in folk and pop music are culturally specific. In Mexico, for example, the 3/4 time signature is commonly used in "música ranchera,” the foundation for mariachi and banda, which has its own rich associations and meanings. I’ll keep my focus here on U.S. pop music, with a jazz interlude. No country music under consideration, either, though country has a long and beautiful waltz tradition, including some crossover successes like Patti Page’s hit recording of “Tennessee Waltz.”

A Long Time Coming

In 20th-century pop, waltz time took the form of torch songs, crooner ballads, jazz waltzes, and more. And though most of us would never say something like “doo-wop waltz,” R&B went all in on triple meters.

Arpeggios, it’s worth noting, fit 6/8 time like a glove, pulsed by a bass note accent at the arpeggio’s beginning. Think of Elvis’s 1961 cover of “Can’t Help Falling In Love,” Brian Wilson’s 1963 “In My Room,” or Al Green’s 1972 version of Robin & Barry Gibb’s “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart?”

Triple meters weren’t only for arpeggiated love, heartache, and introspection. Songs in three offered social commentary and created community. When Sam Cooke heard Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” (in four time), Cooke asked himself why he hadn’t written it. In 1963, he wrote his own protest masterpiece, “A Change Is Gonna Come,” in 12/8 time.

The song’s orchestrated arrangement makes a dramatic and powerful statement, with strings and horns soaring as richly as Cooke’s own hypnotic voice. While the song’s lyrics look to a better future, its triple meter swings and sways, expands and unites, inspires and soothes—all of which helped to make “A Change Is Gonna Come” a leading civil rights anthem.

Dylan wrote his 1963 folk anthem “The Times They Are A-Changin” in 3/4 time. It was telling that in 1965, The Byrds covered the song in 4/4, shifting meters with music’s changing times.

Before we explore this shift further, let’s look a bit at jazz’s handling of triple meters.

A Jazz Interlude

Bebop put 4/4 time in the driver’s seat, meaning jazz started sidelining triple meters in the 1940s, well before rock marginalized them in the 50s and 60s. The free-leaning drummer Sunny Murray remembered arriving in New York in the 50s to find beboppers refusing to play in three altogether. Swinging “Blue Danube” was tired old Tommy Dorsey stuff for squares.

Except that improvisation’s adaptive and just plain stubborn spirit meant jazz never entirely gave up on playing in three. Fats Waller first recorded his “Jitterbug Waltz” in 1942. The tune’s cascading melody made it a favorite of jazz musicians, who covered it faithfully over the decades, even when bebop made playing in three unpopular. I love too many versions of “Jitterbug” to choose just one; the musician Sam Spear collected a few major covers here, all worth hearing.

An early modern jazz composition in 3/4 was Herbie Nichols’s “Bebop Waltz,” first recorded in 1951 by the transcendentally hip Mary Lou Williams as “Mary’s Waltz.” Williams’ recording helped give Nichols what A.B. Spellman called a “modest reputation as a composer of unusual talent whose compositions had never been used.”

On the 1956 album Sonny Rollins Plus 4, Sonny recorded his own jazz waltz, “Valse Hot,” which was based on the chord changes to Harold Arlen’s “Over The Rainbow.” Rollins said “Jitterbug Waltz” affirmed for him the value of underutilized meters in jazz. This first recording of Sonny’s “Valse Hot” owes much of its success to the fluid playing of trumpeter Clifford Brown and especially drummer Max Roach, bebop’s preeminent rhythmic innovator.

According to Aidan Levy’s recent Rollins biography, Roach was so inspired by playing in three on Sonny’s recording that he became obsessed with waltzes, testing various tempos and accents, moving the pulse from the first to the second or third beat. The challenge was innovating with waltz rhythms while sustaining a light sense of swing.

Roach’s experiments found enough variety to record the 1957 all-waltz album Jazz in 3/4 Time, a fresh concept for its era. Its six tunes include two originals by Roach and what may be the definitive version of Sonny’s “Valse Hot,” clocking in at an epic 14 minutes. It was as if Roach couldn’t stop until he’d found or created as much genius in triple meter as he had in bebop’s 4/4.

Leonard Feather reviewed Jazz in 3/4 Time for Down Beat:

“The waltz becomes ineradicably established in direct association with jazz. Not as a gimmick. Not as a twisted three-against-four metric device . . . The music played by Rollins, Roach & Co. makes no apologies or qualifications; it is waltz music, and it is jazz, and it makes it.”

Soon there were jazz waltzes aplenty. Dave Brubeck had covered Sammy Fain’s “Alice in Wonderland” with his quartet from the early 50s; he believed that he introduced the jazz waltz concept to his contemporaries. Bill Evans first recorded his “Waltz For Debby” in 1956. Before long jazz had Wes Montgomery’s “West Coast Blues,” Miles’s “All Blues,” Coltrane’s cover of “My Favorite Things,” Toots Thielemans’ “Bluesette,” and Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints” (Wayne was a prolific composer in three). Monk wrote “Ugly Beauty,” his first 3/4 tune, in 1967.

Since the relatively simple 3/4 time signature can bedevil even an accomplished improviser, it’s good to have some tricks for the meter. A standout solo for me is tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley’s turn on Miles Davis’s 1961 title track “Someday My Prince Will Come,” which Brubeck would want me to mention he’d covered first. Here Mobley’s winning approach to the mid-tempo waltz involves pushing his phrasing across bar lines, moving toward beat one of the following measure. Momentum can matter almost as much as accent when playing in three. (Mobley’s is the first tenor solo around 3:10, after Miles)

Jazz of course moved on to other time signatures, most famously with Dave Brubeck’s 5/4 “Take Five.” From there jazz voyaged to the exotica of 7/4 and even 13/8—only prog rock rivals jazz for odd meters.

Still, the jazz waltz abides, with musicians floating the backbeat around to find lyricism, impressionism, variety, and drive in newer tunes like Scott Colley’s “Haze And Aspirations,” Taylor Eigsti’s "Magnolia,” and Camille Meza’s “Waltz #1.”

We’ll close our jazz interlude with one of my favorite waltz covers in recent years: the Branford Marsalis Quartet’s take on Andrew Hill’s “Snake Hip Waltz.”

Four on the Floor

Now back to pop music.

“It's got a good beat and you can dance to it,” went the American Bandstand Rate-A-Record cliche, which was recited like a mantra as those qualities became paramount in rock.

Earlier pop music like R&B had a foundation in eighth note swing, the triplet’s bounce. By the mid-50s, some pop musicians were leveling that bounce, creating a driving chuck-chuck-chuck-chuck of eighth notes. This straighter-eighth feel became the prevailing groove in rock by the mid-60s, though soul music wasn’t quite done with the triplet feel or triple meters.

The primary challenge of rock in three is where to put the backbeat. Rock thrives on 4/4’s clear pulse, with the backbeat landing firmly on two and four. A heavy backbeat on 1 in a 3/4 rock tune easily can stray into polka territory.

Rock music does have its exceptions, songs that use 3/4 and 6/8 time magnificently. As in jazz, experimentation with beat accent often helps. In “Manic Depression,” Jimi Hendrix and drummer Mitch Mitchell put the backbeat on two and three, creating a driving 3/4 blues shuffle that would never be mistaken for a polka.

When Joe Cocker covered Paul McCartney’s “With a Little Help from My Friends,” Cocker’s blue-eyed soul drama got most of the attention (and mockery). The song’s transformation into a 6/8 ballad also helped bring the message home, lending all-together-now sway to its theme of community.

These examples are rarities, though. Rock marched into the 70s on 4/4 time, with most musicians leaving triple meters to soft rock dreamers like John Denver (“Annie’s Song”), Cat Stevens (“Morning Has Broken”), and Billy Joel (“Piano Man”). Jimmy Buffet’s 1974 album title spoke to the state of triple meters in rock: Living and Dying in 3/4 Time.

Lighters In The Air

Still, rock in three would not go gently into that good night. In the 70s, musicians and producers found a way to bring aggressive virility to the ballad, whether in three or four time.

Enter the power ballad.

I’ll admit that I’m helpless before the emotional adrenaline rush of the power ballad. Most of these heart-stirring anthems reached me as an impressionable grade-schooler before I could hear their banality. Even now, the first few measures of an 80s power ballad suffuse my mind, body, and soul with euphoria before I can even think about mounting resistance.

So I look to music historian and leading power ballad scholar David Metzer for reasonable information on this subgenre. Metzer makes a well-supported argument that Barry Manilow (“Mandy”) and Melissa Manchester (“Don’t Cry Out Loud”) launched the power ballad in the 70s. He breaks the power ballad down into a set of musical and expressive formulas. An opening of relatively mild and tender introspection is followed by escalation: climactic key modulations and grandiose symphonic buttressing, for example. There’s sentimentality and uplift galore. Metzer also finds the power balladeers’ forebears in the tortured poets of the Romantic era.

Today’s power ballad debates can have as much escalation as the songs themselves. Still, I’ll go out on a limb here and cite the Eagles’ 1974 “Take It To The Limit” as an early country-rock power ballad in three. Queen kept triple meters alive with operatic power ballads like “We Are the Champions” and “Somebody to Love.” Journey got their teeth into the power ballad and wouldn’t let go. The band’s thick power ballad songbook includes the triple-metered “Open Arms” and “Lovin’, Touchin’, Squeezin’,” a title so corny it hurts to type.

Like other pop subgenres, power ballads haven’t flexed their 3/4 chops nearly often enough for my taste. How much more penetrating would Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart” be in 3/4? Imagine Peter Cetera’s “Glory of Love” in 6/8, if you can handle it.

Beyond and Back Again

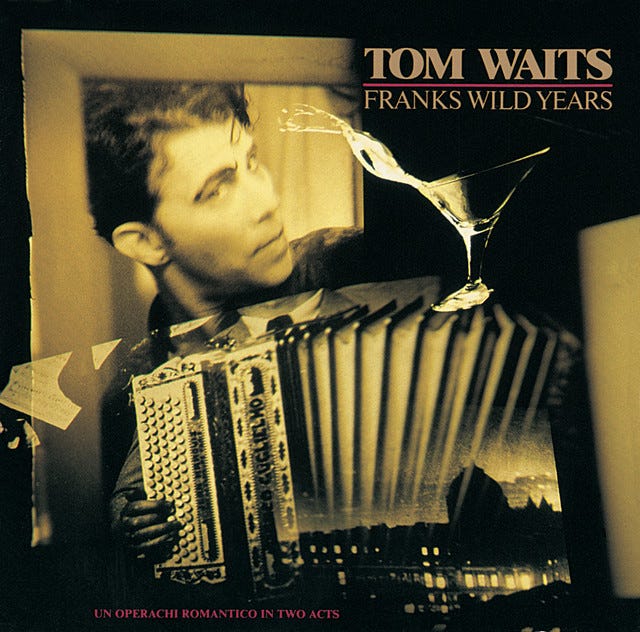

Some 3/4 songs fall into a “beyond” category. The cheerful fatalism of “Que Sera Sera” lived on in the pop waltz, with no songwriter embracing the waltz’s vaudevillian whirl of the absurd quite like Tom Waits. He likes his waltzes wistful, weird, and so lilting they take on an instability: his music feels as if it could spin out of control, fall apart, or go off the rails.

Also, check out Tom Waits/Marc Ribot’s 2018 “Ciao Bella (Hello Goodbye).”

Waltz is a form for turning convention on its head in Kate Bush’s 1979 “Ran Tan Waltz,” where a young mother goes out to philander, leaving her husband home with the baby, with Bush’s music bringing a bizarre cabaret aesthetic to the style. Elliott Smith wrote unusual waltzes that seemed to put the listener inside a music box, with its tiny dancer figurine spinning dreams and regret.

Less of a waltz but leaning hard into its vaudevillian performance tradition is Billie Eilish’s “when the party’s over.” She goes fully expressionistic on the concept of a blue mood.

In another “beyond” permutation, Seal has described his 1994 hit “Kiss From a Rose” as a “strange medieval-type madrigal with R&B stops.” The song’s 3/4 meter appealed to him, as he told Vulture’s Nate Sloan:

“I’ve always loved kind of uncommon time signatures. Not to say that 3/4 is uncommon, but as it pertains to pop music or popular music, I’ve always loved the lesser used time signature . . . I enjoy singing across an odd time signature because I find it quite freeing when you are not being anchored by the one [beat] across 4/4.”

Seal moving the beat around: an old jazz trick, again, in the formula for triple-meter pop success. Plus an oboe solo.

A more restrained alt-rock ballad is the Goo Goo Dolls’ “Iris” in 6/8. This song finds propulsion by accenting 1 and 4, a winning strategy for 6/8 meter in rock. Written, by the way, for Nicholas Cage’s angel character in City Of Angels—and if any actor should inspire an alternative power ballad, it’s Nick Cage.

Three is rare enough that I welcome nostalgia’s rehashing of old styles when they help get new triple-meter songs into circulation. There’s the arpeggiated 6/8 doo-wop of Rihanna’s “Love On The Brain” and the 12/8 gospel soul of Alicia Keys’ mega-hit “Fallin’”—both no less effective for their nostalgia.

Finally, in the “beyond” category we should mention Leonard Cohen’s secular hymn in 6/8, “Hallelujah,” an ongoing hit at singing competitions and weddings (for couples who haven’t really listened to the song).

Cohen’s songbook has more than its fair share of waltzes, an ideal setting for his poetic vulnerability and horniness—call it passion, if you like. Songs like “Famous Blue Raincoat” are so intimate that you almost feel Cohen pressed up next to you, breathing the music into your ear, taking full advantage of the slow dance.

“Take This Waltz,” Cohen intoned, even more to the point of this essay.

Time Is On Our Side

Christmas music is some of our contemporary folk, including songs many of us have known since we were children. Holiday music’s enduring appeal also may have something to do with the triple meter’s heavy representation in both its sacred and secular songbooks. For a month or so each year, classics like “Silent Night,” “O Tannenbaum,” “Silver Bells,” and “We Wish You A Merry Christmas” return to fill the three void.

We need more music in three all year long. As we’ve seen, triple meter is the holy trinity, the spinning waltz, the rolling balance of rock, the unifying sway of group protest, the whirl of the absurd, and the swing of jazz. Given all that music in three offers us, there’s simply not enough of it in the world at present.

I’ve tried to convince my tween songwriter son to compose in three, but he foolishly refuses my advice on all matters of aesthetics and taste. Maybe you’ll write more music in three? At the very least, please share your triple-meter song favorites in the comments below.

Thank you for coming away with me to the land of perfect time, where life is but a dream. I’ll leave you with Norah’s jazz-tinged Texas waltz, one of the 21st century’s highest-grossing pop songs in three. So far.

I'm a sucker for jazz waltzes -- I hadn't even realised, till a musician friend made fun of me for it. My favourite is probably Chick Corea's 'Windows' (the version with Hubert Laws on the flute)

Thanks for your wide-ranging consideration of the "power of 3"! I'll toss two more facets into the mix: [1] the rich, suave and powerful drumming approach that Elvin Jones brought to triple meters. Every decent jazz drummer of my generation knows what's meant if you say "an Elvin 3" -- or, for that matter, a (Bernard) Purdue shuffle; [2] as I understand it, the Cameroon groove called "bikutsi" is commonly a type of 12/8 feel (four triplet quarter-notes per bar, a cousin of swing and shuffle feels). But check out what virtuoso Cameroonian drummer Brice Wassy (credits include Salif Keita and Jean-Luc Ponty) created in his piece "Flip Stories", which is a "bikutsi in 3" (three triplets per bar)!: https://youtu.be/E8z5eaxQtIs