Hard Truths for Poor Artists: Merit Is a Trap

For happiness and success, don't wait around for your good work to get its due

Hello again, friends. Happy summer. We’re back with the least asked-for series on Substack! The series that makes you bitter over your misfortune or guilty for your privilege.

But I kid. Readers have been asking when I’d return with another installment of Hard Truths for Poor Artists. One of my goals is to move the discussion of money in the arts beyond victimhood stories or grit and determination narratives by essaying underconsidered subjects with some nuance. Earlier posts are foundational:

The forced error of student loans and the double bind of college for poor artists

The magic of affinity in arts careers and pitfalls of the MFA for poor artists

How artists can move from glittering cultural capitals to smaller, more affordable spots, Part 1 and Part 2

Most of us don’t refer to ourselves as artists in daily life. That would be insufferably pretentious. I call myself a writer. I use the term artist to give these posts broader relevance.

Merit Is a Trap: For happiness and success, don’t wait around for your good work to get its due

By now, most of us are aware that artistic merit, like all merit, is subjective, conditional, and contextual. No truly objective measure of excellence exists for any artistic genre. Back in 1949, Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Joseph Downs shared a common dismissal of Southern art, remarking that “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.” Such contempt is uncommon and unacceptable today. Most artists and artistic gatekeepers are now quick to acknowledge that fantastic art is made everywhere and that determining what makes art fantastic is a variable and slippery business.

Recognizing artistic merit’s subjective nature doesn’t stop many artists from believing in meritocracy, or a world where people should get success or power because of their abilities. Shaking the belief that great art guarantees success can be hard to do. Especially in the U.S., where the Protestant work ethic—work hard, get ahead—often conflates skill and effort, many artists still believe good work will find glory in a promised land of renown. In a few rare cases, it does.

This matters because merit-obsessed artists are some of the most discontented motherfuckers around. Seriously. The unhappiest artists I know are those with an absolute belief that quality work should always find profound appreciation and wide acclaim on its merits alone. They’re often disappointed. Angry. Bitter.

Those of us from underprivileged backgrounds tend to have an especially fraught relationship with merit. When we first start making art, we tend to lack any social capital whatsoever. No family connections or resources; none of the skills and relationships developed through summer arts camps or prestigious institutes. Our only way in seems to be standing out on merit with high test scores, early contest wins, etc. We cling to merit like a life raft because it’s how we made the rough crossing to a new world. Conditioned in childhoood to believe in the magic of exceptionalism, we can’t let it go. We assume exceptional work will always overcome the odds. This merit obsession can block our ability to recognize and leverage factors that intersect with merit to enable success.

My artist friends from more comfortable backgrounds tend to have a more well-adjusted relationship with merit. Not that more privileged artists are lacking in excellence. In the very first Hard Truths post, we established that merit and privilege are not mutually exclusive. Growing up with structural advantages trains artists to enhance the value of their work with timing, marketing, and other strategies. They’re more willing to work the system to give their well-made art its greatest chance of success.

I’m speaking in general. We know privileged artists who are merit obsessives and underprivileged artists who are not.

This is not a defeatist message. I’m not giving up on merit or artistic exellence so much as recognizing how it intersects with other factors. Most arts careers achieve liftoff with a combination of talent, ambition, strategy, timing, and luck.

Money boosts merit and can create the illusion of it

Emerging artists should know just how many opportunities are self-funded, even when merit enables them. We often discuss the luxury of taking an unpaid internship. It doesn’t stop there. An artist with a sexy overseas lecturing gig may secure it through accomplishment but also by funding their own travel. Book tours are often financed by authors, at least in part. Exhibits and showcases that appear entirely merit-based may be pay-to-play. Funded artist residencies still often require resources to care for family, pets, and property back home. Receiving a merit-based award may involve a substantial investment in formal wear and accommodation for the awards ceremony. Independent incomes fund many, many arts careers.

The Guardian recently reported on the problem of working-class musicians getting priced out of touring, because they can’t afford to treat it as a “loss leader.” This applies to not only upstart garage bands but groups “playing to thousands of fans in a sun-drenched festival field, signing a record deal with a major label or playing endlessly from the airwaves.” Touring, the article notes, is rapidly becoming a privilege of moneyed musicians.

On smaller creative music scenes, the burden of filling even a modest venue can fall entirely on a musician. Someone’s ability to bring in 15-20 friends and family who’ll spend $100/each on food and drinks can matter to booking decisions more than how well someone plays music. What’s a poor, merit-obsessed musician to do? Adapt by marrying a bank executive. But seriously: invite friends with and without money to gigs while continuing to play as well as they can.

This past fall, a writer acquaintance tried to crowdfund a walking trip in Europe. She ran out of money and steam, returning home without completing her trip. I felt she’d been misled. Many stories of people covering some challenging epic distance neglect to mention the support, financial and otherwise, that they have on their journeys. Social media influencers create an illusion of fueling expensive travel on gumption and derring-do when many of them have independent incomes. Support is out there if you qualify for it: I’ve rarely taken a trip overseas that wasn’t funded by an assignment, residency, or sponsoring institution of some kind. But if we all had to crowdfund overseas trips and arts projects, most of us would fail.

We should be more transparent about the money required to seize many merit-based opportunities in the arts.

Merit obsession can preempt marketing and publicity

I’ve been guilty of not describing my books well because I thought they should get across on their own merits, without any marketing hype. Same for holding back on publicity. We want to believe the literary world is fundamentally a meritocracy in which books find their readers on the strength of the writing alone.

Marketing and publicity are not cheating. We live in an attention economy. Here on Substack, for example, headlines that fear-monger the zeitgeist, offer boldly contrarian flavor, or boast an almost religious promise of big-picture solution tend to do best. The psychology of these headlines says read this or fall behind, miss the boat, be a blundering idiot. Some of us may shrink from these headlines, viewing them as too pandering. But do such headlines undermine the value of posts? They do not. Such headlines grab the attention of readers who can then discover a post’s merits. If we want to grow an audience for substantive posts, why resist effective labels?

We don’t want to go too far with marketing or publicity, though. A few years ago, an artist arrived in town with a message that careers were all about hustle. He hustled up some press attention and buzz until a failed audition sent him packing. Both hustle and merit matter.

Merit obsession can make us heedless of good advice

When artists esteem exceptionalism out of proportion, we can become heedless of good advice. Advice, we may believe, applies to other people, not us. My generation of young artists devoured Meghan Daum’s epochal 1999 New Yorker essay “My Misspent Youth.” Yet I didn’t think this essay applied to me because of minor distinctions between Daum’s experience and mine. Besides, I was someone who overcame the odds.

Her cautionary tale did apply to me. Very much so.

Merit obsession can make an artist resistant to timing

Timing isn’t everything, but it’s something. Gawd bless artists for having the character to work beyond the popular. Insisting on pure, timeless aesthetics makes us miss anniversaries, trends, or other timely factors that could bring attention to our work. Well-adjusted artists create from genuine inspiration and then ask, “How does my work align with this cultural moment?”

Timing within a career matters as well. In Colson Whitehead’s novel John Henry Days, culture journalists share some black humor around “the three discrete schools of puff” or profile pieces: Bob’s Debut, Bob’s Return, and Bob’s Comeback. The artistic debut and comeback are especially beloved narratives. Perennials, tried and true. If you’re a shiny new artist, why not play up the debut angle? If you’re a few rounds into art-making, maybe frame your work as a comeback. If you’re 50, maybe you’re a wise veteran, an elder statesperson.

Mediocre artists who are unfairly given merit-based opportunities can develop serious careers

Good artists may not be rewarded for merit. Mediocre artists may win what they don’t deserve, and then with the win’s resources grow into serious artists. Also, rewards people receive are often taken as evidence of their competence. Artists can reach a cruising altitude of renown at which any new work is lauded regardless of its quality.

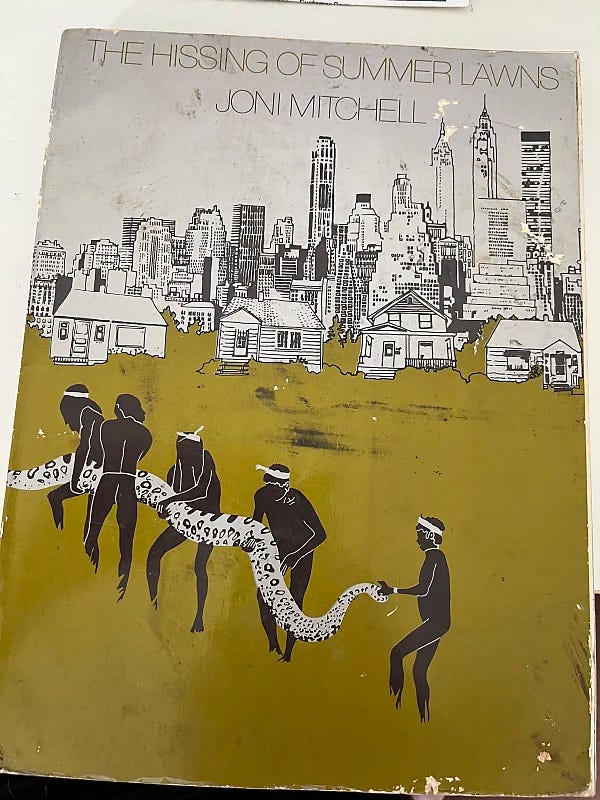

None of this is fair. For merit obsessives, who are often also comparison junkies, such unfairness can be disabling. Before Joni Mitchell’s aneurysm, she was frankly stuck in a merit-obsessed cul-de-sac, angry that her better work was underrecognized, bitter that lesser artists were celebrated regardless of their work’s quality. She wasn’t wrong—merit obsessives often are correct—but she was profoundly unhappy. Now she hobnobs and performs with artists of various calibers. She also seems much happier.

A case study in merit and marketing

The GRAMMY Awards occasionally recognize a favorite artist of mine. I’m delighted when a musician I love happens to win a GRAMMY, garnering press, performances, and other opportunities. Generally, though, the GRAMMYs don’t have much to do with my private musical meritocracy. They favor household names over the creative mid-level musicians I usually prefer.

I thought everyone had lowered their expectations for GRAMMY recognition. So I was surprised when a certain GRAMMY win shook the jazz world a few months ago. The familiar refrain that other nominees had been more deserving devolved into whispered conspiracy theories: The winner had bought the award by devious and probably illegal means. The fix was in!

I racked my brain wondering what this illicit GRAMMY activity could have entailed. Sponsoring recording academy hot tub sessions with escorts and microdosed goodies? Maybe, though GRAMMY campaigning rules discourage such decadent enticements. Perhaps some juicy story of backroom GRAMMY bribes is waiting to be uncovered. I suspect the truth is more pedestrian.

As far as I can tell, the winner hired a team familiar to recording academy members, a team highly adept at positioning and promoting artists. The winner’s sin seems to be having the resources and inclination to work the system. Given some money, working the system is smart in the GRAMMY universe of popularity and spin. What if the other nominees had proceeded as if their merit guaranteed nothing and had promoted their own nominations, even a little? The winning outcome may have been different.

Moving beyond merit obsession is the key to a long, happy creative life

Why do we make art? At some point in our careers, most of us will need to develop motivation beyond any validation whatsoever. If we find ourselves, as I have, living in a place where our hard-won accomplishments suddenly have negative value, how will we keep working? What will drive our work in the years between youthful artistic debuts and end-of-life retrospectives, those periods when our work falls out of favor or relevance? Showing up for art every day of our lives takes our creativity farther than any recognition ever could. Most artists not only want but need to keep working all their lives at the thing they love. For happiness and endurance in art, moving beyond merit obsession is key.

If you do win a nomination or award, accept it graciously and get back to work as soon as possible.

Coda: Merit Hits Close To Home

Two years ago, my then-10-year-old son won a kids’ songwriting contest. Finishing a song and preparing it for performance was a valuable experience for a kid his age. Still, I encouraged him not to enter last year. This contest win came with a cash award and festival performance. I didn’t want him to associate songwriting with contest spoils or external validation; I wanted him to go on exploring songwriting as artistic self-expression. He skipped last year’s contest and then asked to enter again this year.

As we were recording his song entry late last month, he said, “Imagine if I do all this work to submit a good song and then don’t win.”

My merit alarm went off. “Honey, you’ve done a great job,” I said. “Your song is poetic, melodic, expressive, and imaginative. That doesn’t mean it will win.”

I said it was possible someone in his 12 and under category had written a better song. This was an exciting prospect. He’d have a songwriting peer, a potential friend.

I said the judges were different this time, and we didn’t know what they’d be listening for this year. They might want more twang. They might be swayed by someone’s angelic singing voice and not care so much about the quality of their lyrics or music. They might not want to give the award to someone who’d won before, even if he’d taken a year off.

“They might give it to a nine-year-old girl who sings about her kitten because she’s so cute,” my husband said.

“Awwwww,” I said. “I’d want to see that. Kitten song! My heart is melting just thinking about it.”

“You always say the best songs have music and lyrics that work together to create meaning,” the 12yo said. “What if someone wins with a song that doesn’t even try to do that?”

“They might,” I said. “Everyone doesn’t necessarily care about the stuff we do in songwriting. You know about merit, right? What people think is good varies so much. Even if there were some common idea of merit, it wouldn’t always come first in art. There are other factors. That’s why we just keep writing or making music or painting or whatever. No matter who recognizes the value of our work. Showing up for art is what counts.”

“Showing up and doing the work is what counts,” the 12yo recited. “Like I’ve never heard that from you before.”

On Friday, we went to the Meadowgrass Festival in Colorado’s Black Forest for the contest winner’s announcement and performance. Meadowgrass is a cozy festival with a thoughtful program and warm community spirit; the songwriting contest is named after its founder, Steve Harris. My sister-in-law Beth, an accomplished batik artist, drove up from her studio/gallery for the occasion. If the 12yo won again, he’d perform his song an hour or so after the announcement. The 12yo’s Alvarez acoustic, favorite picks, a nice shirt, and a thermos of hot tea with lemon and honey were packed in the car. Just in case.

My son was announced as the second-place recipient. We congratulated him and waited for the first-place winner to perform, ready to hear and praise what might have distinguished her song or performance. When the time came, though, they announced that the 12 and under winner hadn’t turned up that day and wouldn’t be performing. The 13-18 winner took the stage.

“It’s odd that they’re having the older kid perform first,” the 12yo remarked.

“You didn’t hear?” I said. “The 12 and under winner didn’t make it here today.”

“She didn’t even show up?” he asked in disbelief.

It was the only time I saw disappointment flicker across his face that day. He’d been fine with coming in second. What bothered him was not getting to hear the song that had won over his—hearing that winning song was the sole feedback he’d get from the judges. Even more important, we’d taught him that showing up for art is what truly matters. This first-place winner didn’t show up for the performance and still took the top prize. What am I even doing here? I saw the 12yo thinking. Why show up at all?

“Can we go home?” he asked.

Getting him out of there was a good idea. This situation had the makings of irremediable disillusionment.

“Sure,” I said and started folding up my chair. “Maybe ‘Second to a Ghost’ is your next song?” I joked, to lighten the mood.

“What if the winning song was AI?” the 12yo joked back. “That would explain why she didn’t show up.”

His kidding around meant he was okay. Still, for the good of his songwriting soul, we’ll probably move on to opportunities where he can learn more from participation.

The next morning, the 12yo had his guitar out as usual and was playing along to recorded songs by ear, testing out their chords, melodies, and rhythms. “I’m studying what makes some of my favorite songs good,” he told me. “Then I’m seeing how much they sound like other songs that came out around the same time. I’m getting ideas for new ones of my own.” A typical enough project for him. I was relieved.

He’s asking the right questions for a long, happy creative life: Why do I love this art so much and think it’s good? What else may have contributed to its success? What can I create today?

If he keeps showing up for music regardless of merit outcomes, he may keep at songwriting long enough to realize his full potential. His art might just last a lifetime.

This is my favorite column in this series yet, Michelle I love it that your son got back to work the next day!

Michelle , what a beautiful, meaningful, thoughtful, inspiring piece of writing. Though you may not be comfortable with the appellation, you are very much an Artist In my book. I was moved by both your insights and your parenting.

One of my students today stopped me to say that they’ve made the decision to switch their major from music education to jazz performance, and to ask what I thought of that decision. I think they were seeking some validation, which I was happy to supply—they are remarkably talented. And some reassurance, which is a little more complicated to provide. I’m excited to share this post with them because it says so much of what I really want them to reflect on and hold as they try out this new picture of what their lives might be. Gratitude 🙏🏾